Chances are the Troubled Families programme will ultimately be judged a success by the government.

In an announcement last week the Department for Communities and Local Government claimed that the programme was 'on track' at the halfway point. Over 62,000 families were 'being worked with' while 22,000 had been 'turned around'.

The government has committed itself to 'turning around' 100,000 families. At the halfway point they therefore have four-fifths of their target families still to 'turn around'.

Undeterred, Eric Pickles, Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government expressed himself as 'delighted' at the progress, which rather makes one wonder how he would have felt had they been closer to 'turning around' half their target families.

'Councils', Mr Pickles added, 'are making great strides in a very short space of time, dealing with families that have often had problems and created serious issues in their communities for generations. These results show that these problems can be dealt with through a no nonsense and common sense approach, bringing down costs to the taxpayer at the same time.'

What are we to make of these claims?

What is a 'troubled family?'

Let's start with what is meant by a 'troubled family'. As a report yesterday from the National Audit Office (NAO) explains, the government bases its definition on an analysis of the Family and Children survey of 2005 by the Cabinet Office.

According to this estimate, 2 percent of the United Kingdom population - some 120,000 families with dependent children - had at least five of the following characteristics:

- no parent in work

- poor quality housing

- no parent with qualifications

- mother with mental health problems

- one parent with long-standing disability or illness

- family has low income

- familiy cannot afford some food or clothing items.

The estimate does not in fact bear much scrutiny, as social exclusion expert Ruth Levitas and the BBC Radio 4 'More or Less' programme pointed out last year. The definition does, however, attempt to map some of the fundamental disadvantages faced by families in crisis: poverty, inadequate housing, health problems, worklessness.

The criteria for inclusion in the Troubled Families programme has little to do with this definition. In place of the Cabinet Office's seven characteristics of disadvantage is a far narrower set of criteria:

- One adult in the family on out-of work benefits

- Households with at least one under 18 with a proven offence, or any member of the household subject to an antisocial behaviour intervention.

- A child in the household with a record of school exclusion and truancy.

Local authorities participating in the programme also have the discretion to decide on a local factor that can be applied. According to the NAO 'over 50 percent of local authorities used domestic violence or abuse, drugs, alcohol or substance misuse, and mental health for their local criteria'.

As the table below illustrates, the relationship between the original definition the government used to draw up its estimate of 120,000 'troubled families' and the criteria for inclusion in the Troubled Families programme is almost non-existent.

What is a troubled family?

| The original Cabinet Office analysis of characteristics of a troubled family | Criteria for inclusion in the Troubled Families programme |

| No parent in work | One adult in the family on out-of-work benefits |

| Poor quality housing | |

| No parent with qualifications | |

| Mother with mental health problems | |

| One parent with long-standing disability or illness | |

| The family has low income | |

| The family cannot afford some food or clothing items | |

| Involvement in youth crime and antisocial behaviour | |

| Children of school age not in school |

'There is', the NAO observes with characteristic understatement, 'a mismatch between the criteria the Department used to calculate the total number of families at which its programme is targeted, and the criteria for identifying the families in each local authority and then rewarding positive outcomes'. Quite.

Lumpy implementation

The effects of this mismatch are far from insignificant. A fifth of local authorities that spoke to the NAO said that the government's criteria for inclusion on the Troubled Families programme 'potentially excluded some families with multiple challenges in their area from the programme'.

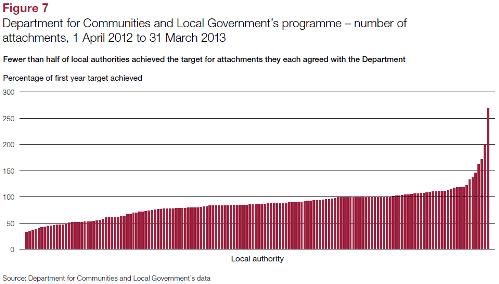

Unsurprisingly, implementation of the programme has been lumpy and inconsistent across England, as this graph from the NAO report illustrates.

Unsurprisingly, implementation of the programme has been lumpy and inconsistent across England, as this graph from the NAO report illustrates.

Some local authorities have taken to the Troubled Families programme with alacrity, far exceeding their target for the number of attachments to it. Others have been far less enthusiastic. Indeed fewer than half of local authorities have so far achieved the target for attachments agreed with the government.

If, and it is a big if, the programme is 'on track', this is because a relatively small number of local authorities have made a disproportionate contribution.

Defining success

The incentive for local authorities to participate is the payment of £3,200 (falling to £2,400 in 2013-2014 and £1,600 in 2014-2015) for each family attached to the Troubled Families programme. An additional £800 will be paid for each family 'turned around' by the programme.

So what does a successful 'turn around' look like?

On the face of it, the measure is simple. A family has been 'turned around' if progress has been made on all three of the criteria for inclusion on the programme: fewer school exclusions; reduced antisocial behaviour; reduced offending. Local authorities will also receive an additional payment if members of the family are attached to an employment scheme.

However, a family selected for the programme via the fourth, locally defined criterion, is also deemed to have been 'turned around' if only one of the three criteria for success (on youth crime, antisocial behaviour and school exculsions) has been met. Alternatively, if only one adult in the family has moved from out-of-work benefits into work, the entire family has been 'turned around'.

The potential for local authorities and national government to game the system are obvious.

Success in tackling truancy and school exclusion, for instance, include the case of a previously non-attending child reaching school leaving age. How many local authorities are targeting families with 15 and 16 year old children, one of my colleagues observed earlier today. Families in which an individual would have got a job anyway, regardless of any Troubled Families intervention, will also class as having been 'turned around'.

A cruel hoax

The government will continue to claim success in 'turning around' the lives of troubled families. Meanwhile, in the real world, some five million children in the UK are growing up in absolute or relative income poverty, as the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission pointed out in a report in October.

Food poverty - one of the key measures of family crisis highlighted by the Cabinet Office and ignored by the Troubled Families programme - risks creating a 'public health emergency', according to health experts who have written to the British Medical Journal.

For these families, facing adversity and hardship on a daily basis, the Troubled Families programme is little short of a cruel hoax.