Why are 89 per cent of people on the Manchester Police gang database from a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic background?

There are an increasing number of research and evaluation reports, which document the prevalence of gangs within England and Wales.

Whilst much of this reinforces a widely held view of the serious ‘risks’ and harms posed by such young people, other studies have questioned the value of the gang label for ‘making sense’ of the problems experienced by young people.

In 2013, colleagues and I published a report for Manchester City Council profiling the social, personal and criminogenic ‘needs’ of young people who were

(a) identified as a ‘gang-concern’ or

(b) had perpetrated serious violent offences (SYV).

The project was essentially a quantitative study drawing data from criminal justice case management and monitoring systems. That Greater Manchester Police were able to provide access to a list of people defined as a ‘gang-concern’, was a crucial step in facilitating the overall research process.

Stark and contradictory findings

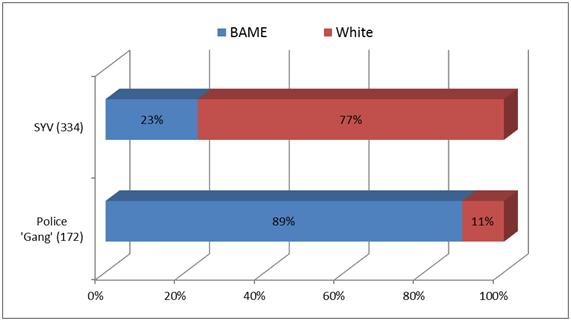

Early into the research we were struck by the stark over-representation of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic people registered on the dedicated police gun and gang unit list.

This was even more perplexing when compared to the ‘race’ and ethnic profile of those convicted of SYV, where 23 per cent of the young people were identified as belonging to a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic group. Particularly since the two cohorts are drawn from the same geographic area.

This was even more perplexing when compared to the ‘race’ and ethnic profile of those convicted of SYV, where 23 per cent of the young people were identified as belonging to a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic group. Particularly since the two cohorts are drawn from the same geographic area.

Locally, a SYV offence is defined as the committal of murder, attempted murder, manslaughter, wounding, actual bodily harm and/or grievous bodily harm by people under 25 years of age. Through analyses of offence type, we found that young people in the SYV group committed offences of a more serious nature when compared to the ‘gang-involved’ group.

Despite populist claims to the contrary, the ‘risk of harms’ posed to the public, community and other young people, was not restricted to the ‘gang’, but was both more prevalent and significant for the SYV cohort.

Finally, of those listed on the police ‘gang’ list, we found that not all were ‘gang’ members!

Officers disclosed that through ‘intelligence’ some young people were identified as ‘gang associates’ or ‘at risk’ of gang involvement or behaviour.

It was perhaps unsurprising then that 40 ‘gang-registered’ individuals had no previous convictions and a further 39 had no convictions within the three years prior to the commencement of the study. Of course, we accept that conviction is a proxy measure for actual offending behaviour and that those individuals with ‘no convictions’ may have been involved in offending behaviours. However, given the levels of police ‘intelligence’, it is likely that where such individuals were engaging in gang related criminal activity they would quickly come to the attention of the Police.

This uncomfortable finding reflects one of the fundamental problems of UK gang research, where even the very definition of the gang is subject to dispute. Added to this is the patent failure of criminological research to derive a correlation between ‘gang’ involvement and the perpetration of serious offences.

Challenging racist policy and practice

At its simplest level, it is my assertion that the disproportionate number of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people in Manchester on the police gang list reflects the discretionary and covert policing practices of the dedicated gun and gang unit.

The findings of our research offer a timely rebuttal to the simplistic assumption that the racial composition of the ‘gang’ reflects the racial composition of the communities within which the ‘gang’ exists. The ‘gang’ label does not derive from the committal of an offence. It is a label devoid of value. An arbitrarily applied term, which conceals the acute, personal, social, emotional and structural problems endured within Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities.

Yet the ‘gang’ label curiously persists, stealthily attributed to the same communities where once the folk devil of the ‘mugger’, the ‘pimp’ and the ‘yardie drug dealer’ once resided. The harms perpetrated through SYV transcend racial, ethnic, gender, age and class lines. Violence, in both its overt and hidden forms, does not discriminate.

Criminal justice strategies conceptualised around a racialised construct of the ‘gang’ will never be effective in arresting levels of serious violence, but can only serve to perpetuate and legitimise the racist over-policing of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people and communities in England and Wales.