On January 9 the Ministry of Justice published Transforming Rehabilitation, its latest plans for the management of convicted lawbreakers in the community.

The proposals can be downloaded from the Ministry of Justice website.

'The case for change and the principles and rationale for extending competition of probation services and effective offender management remain compelling', the document claims. The new proposals can be summarised as follows:

1. The 'majority of community-based offender services' will be put out to competition to the private and voluntary sector, with providers paid according to the results they deliver.

2. The role of the probation service will be significantly reduced. In the future it will focus on initial risk assessment, advising courts on sentencing options and the direct management of convicted lawbreakers deemed to be 'high risk'. The Probation Service will also 'have responsibility for ensuring that contracted providers are effectively managing the risk of harm posed to the public'.

3. There will be a major overhaul of the existing Probation Trust structure. The government's March 2012 consultation, Punishment and Reform: Effective Probation Services, envisaged the 35 Probation Trusts commissioning offender management contracts. Transforming Rehabilitation claims that 'responsiveness to local needs does not necessitate local commissioning'. Contracts will be commissioned nationally through '16 contract package areas' that 'cover geographical areas larger than the current Probation Trusts'. This 'will require fewer Trusts of a different structure (such as a single national probation trust or direct delivery on behalf of the Secretary of State)'.

4. Post-release supervision of released prisoners will be extended to those given sentences of less than 12 months.

Transforming Rehabilitation closes with a series of questions related to the operational design of the proposed new system, as well as some broader questions on further reform.

In the spirit of inquiry, I thought I would pose five questions of my own about the government's proposals.

Question one

Will the government commit to genuine transparency - including financial transparency - on all contracts to enable democratic scrutiny?

Transforming Justice claims that greater competition will deliver savings, citing 'the estimated savings of £25m over the four-year life' of the London Community Payback contract as proof.

There is a long history of public sector contracts being shrouded in secrecy, with many of the promised savings never materialising. In its August 2012 report - Implementing the Transparency Agenda - the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee wrote:

This Committee has previously argued that it is vital that we and the public can access data from private companies who contract to provide public services. We must be able to follow the taxpayers' pound wherever it is spent... Data on public contracts delivered by private contractors must be available for scrutiny by parliament and the public.

Given the importance the government places on making savings on contracts, and the risk inherent in a payment by results arrangement, greater transparency has a key role to play in ensuring proper oversight and accountability by providers.

Question two

Why does Transforming Justice claim that 'the offender management system... is failing' to reduce reoffending when the government's own data shows that reoffending rates have reduced over recent years?

In his Foreword to Transforming Justice the Justice Secretary writes that 'We now need real reform of the criminal justice system to tackle the unacceptable cycle of reoffending... We can't simply carry on in the same way hoping for a different result'.

The Ministry of Justice's own data tells a different story. Comparing adult reoffending between 2000 and 2010 the data shows that adult proven reoffending was 3.1 percentage points lower in 2010 compared with 2000, after controlling for the differing characteristics of convicted lawbreakers. The average number of reoffences was also lower, by 15.3 percentage points. The proven reoffending rates for juveniles was also lower, by 1.4 percentage points when 2010 was compared with 2000. The average number of reoffences was down by 13.5 percentage points.

These may appear to be modest reductions, but modest reductions is what the Justice Secretary is looking for with his proposed reforms. As he told the BBC Radio 4 Today programme on January 9:

I am not expecting overnight some dramatic drop in offending but some steady year-by-year decline in offending.

Measuring reoffending is an inexact science; more will offend or reoffend than are ever caught. But given the weight the government places on measuring reoffending it is striking that the rhetoric in Transforming Rehabilitation is out of step with what its own data claims.

Question three

Given these steady year-by-year declines, why is the government intent on unleashing a potentially risky and costly upheaval of the existing system, rather than investing in improving it?

According to Transforming Rehabilitation what is needed is:

a system where one provider has overall responsibility for getting to grips with an offender's life management skills, coordinating a package of support to deliver better results.

Currently there is such a system. It is called the Probation Service and it is directly responsible for the supervision of the vast majority of individuals serving sentences in the community. It also undertakes the supervision of those who have received prison sentences of more than 12 months.

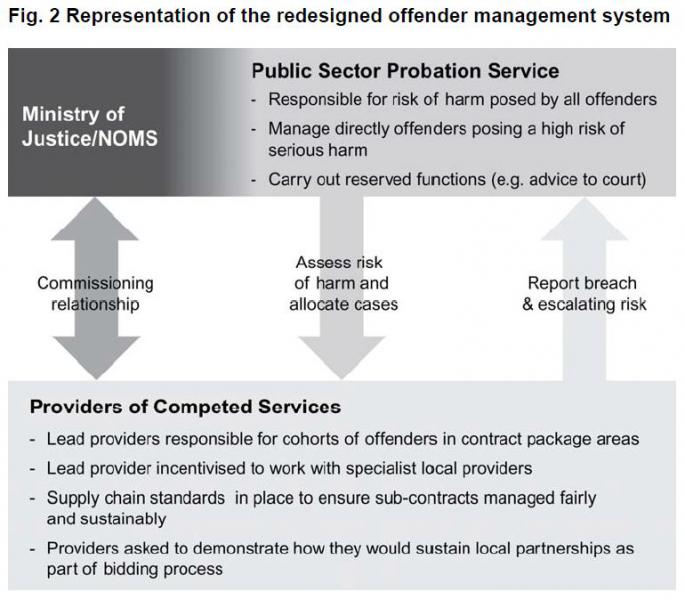

Under the complicated system the Ministry of Justice proposes the 'great majority of community sentences and rehabilitation work will... be delivered by the private and voluntary sectors'. These providers will be accountable to the Ministry of Justice, as the commissioner, and to the Probation Service in relation to risk management. Contractors will also be expected to integrate effectively with a range of local structures and services. The complexity of these new relationships is only partially captured in the figure below, from page 25 of Transforming Rehabilitation.

Question four

Why is the Ministry of Justice trying to shoe-horn the probation service into a structure designed to suit private contractors, rather than taking a strategic view on how it can best be organised to deliver on its local and national responsibilities?

In 2011 the House of Commons Justice Committee expressed concerns about the earlier attempts by the Ministry of Justice to commission the community payback contracts via large geographical lots that bore little or no relation to Probation Trust areas. The Committee argued:

The very large and incoherent groupings created for the community payback contracts would not be appropriate vehicles for commissioning other probation initiatives, and would undermine links between probation work and other participants in the criminal justice system, such as the police, courts, local authorities and local prisons.

The Ministry of Justice wants to resolve this problem by reducing the number of Probation Trusts, or adopting a new structure. This will inevitably mean that it is more difficult for the probation service to retain its local links and profile.

This appears more to be reform intended to shoehorn the probation service into the logic of commissioning, rather than one driven by a strategic view about how the probation service can best operate in the future.

Question five

Why doesn't the government address the unnecessary resort to short prison sentences, instead of introducing the potentially costly community supervision of those given short prison sentences?

People coming out of prison often need help and support: to find accommodation; secure benefits to which they are entitled; find a job; enrol in education; access health services, and so on. Modest investment to ensure through-care and support might well make sense.

Far better, though, would be to prevent people going into prison for short periods, with all the inevitable disruption and harm it causes to them and their families. A spell in prison remains one of the the most significant causes of crime. The government is trying to solve the wrong problem, rather like the man who digs a hole only to fill it back in again.

In his Foreword the Justice Secretary wrote that 'My vision is very simple'. While he had in mind the simple and clear proposition he no doubt believes is embodied in Transforming Rehabilitation, I fear that there may be some unintended irony at work.