I am a criminal defence investigator at APPEAL, a non-profit law practice, specialising in challenging wrongful convictions and unfair sentences for women in criminal cases.

Despite abundant reporting on the unjust and damaging nature of short sentences (see here, here and here), I have always found it difficult to convince women sentenced to short stints in custody to appeal. An internal project at APPEAL, looking into past cases heard by the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) (CACD), found that of a sample of 268 appeals lodged between 1997 and 2010, only 19 were women, a mere 7 per cent of cases. This is even more concerning when you factor in the decline in the total number of applications to the CACD.

While the number of prosecutions and convictions have declined over the last decade, this alone cannot account for the extent of the fall in the number of appeals. From 2011 to 2019, prosecutions dropped by 15 per cent and convictions by 12 per cent, but the same period saw a 36 per cent reduction in criminal appeals. While the CACD does not report the number of applications it receives by sex, it appears that women may be disproportionately underrepresented in the criminal appeal process.

With the support of the Griffins Society, that funds research into women and girls in the criminal justice system, I set out to answer the question: What barriers do women face in seeking to appeal their convictions and sentences to the CACD?

To answer this question, I analysed letters seeking advice from 132 women in custody as well as surveys of 33 women in prison and 20 legal professionals who had experience of appeals.

My analysis revealed three categories of barriers.

Gendered barriers to appeal

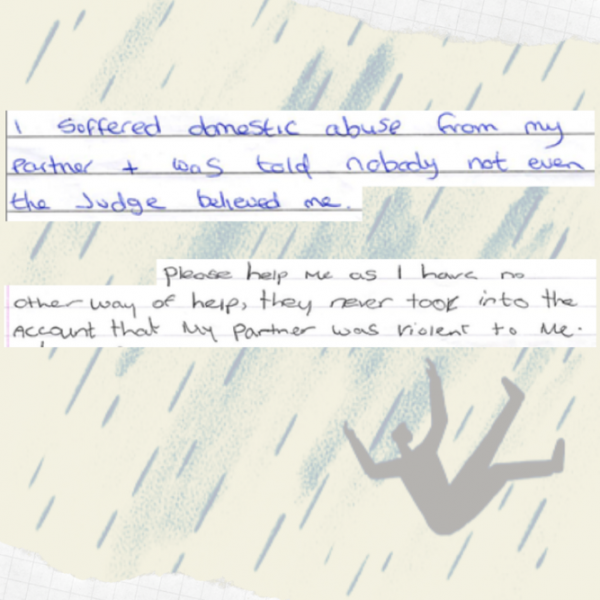

Women often did not reveal their experiences of gendered trauma such as domestic abuse to legal representatives and were afraid of being disbelieved. As a result, such stories often came to light well after conviction and sentence and frequently outside of the 28-day appeal window. Upon arrival to custody, women focused on more pressing issues such as recovering from trauma, poor mental health or addiction and did not prioritise appealing.

Women also did not decide to appeal due to feelings of shame and to avoid placing further strain on their children.

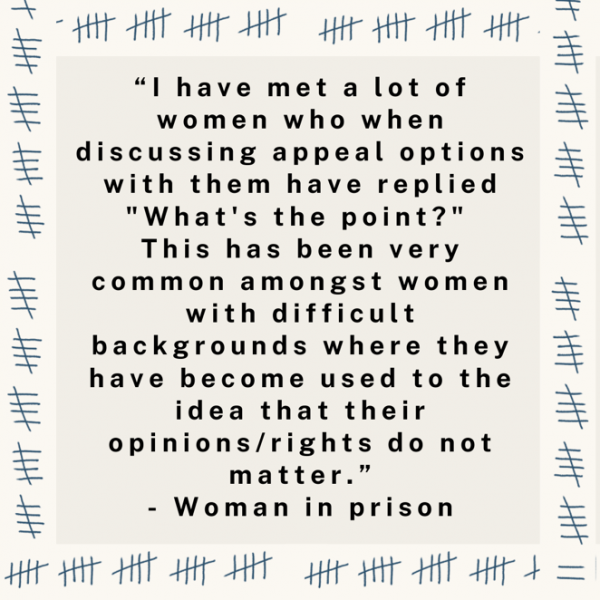

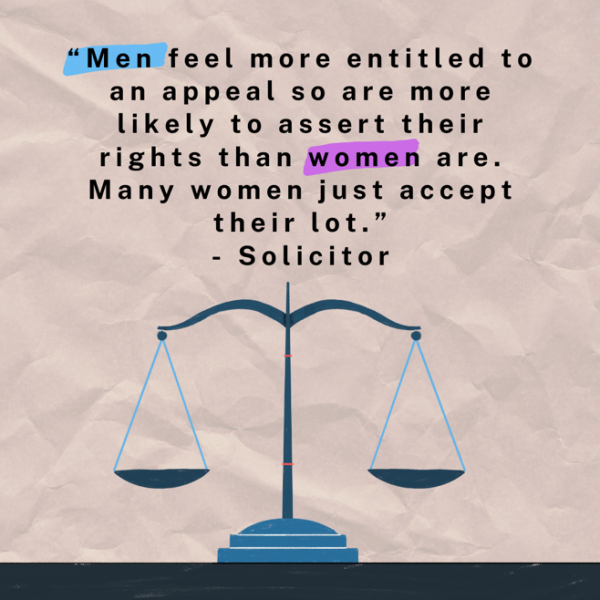

In general, women lacked the confidence to appeal, and had a real fear that the system would not take them seriously and would protect those in power over their rights.

Informational barriers to appeal

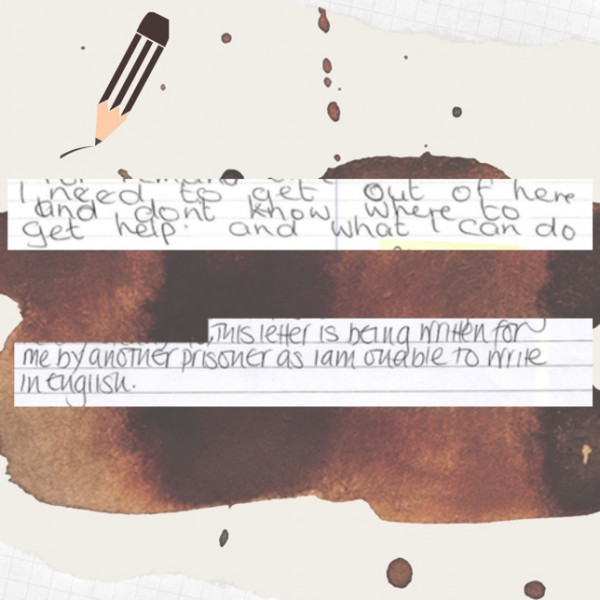

Women lacked knowledge of the appeal process, with more than a third of women not knowing how to lodge an appeal. Women in prison had little access to information or resources, including things as basic as the addresses of law firms or access to printing facilities and paperwork. Women whose literacy or grasp of the English language was poor were, unsurprisingly, even less able to access information.

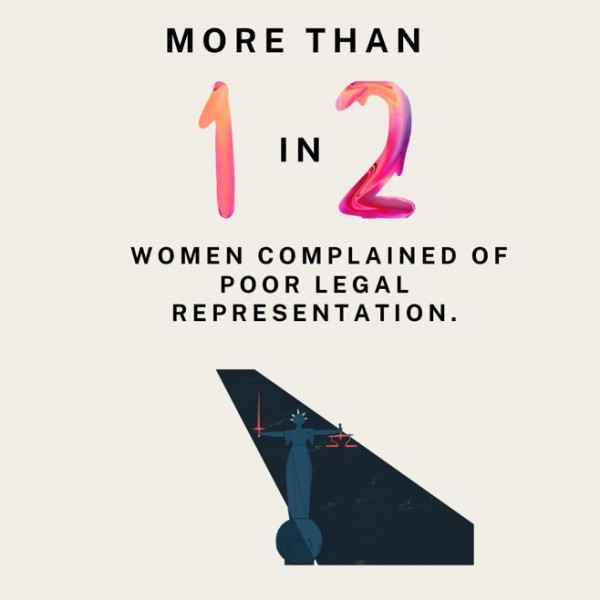

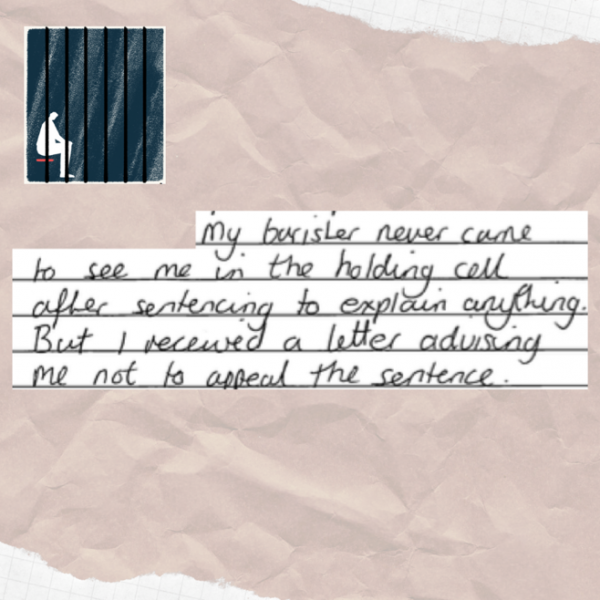

Quality standards of legal representation were also very inconsistent. Half of the women’s letters complained that their legal representatives had in some way fallen short in providing them with adequate advice and advocacy.

Procedural barriers to appeal

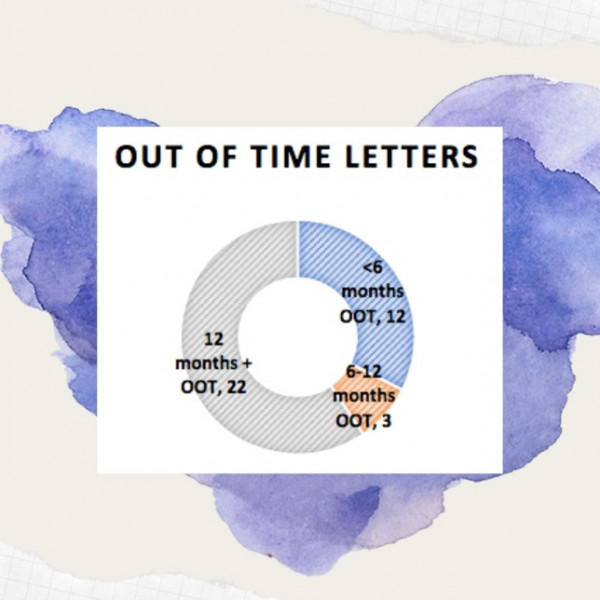

The vast majority - 86 per cent - of women writing for advice on appeal were significantly outside of the 28-day appeal window from the date of their conviction or sentence. Common reasons for explaining the delay were that women were not able to figure out the appeal process in time, and that their mental ill-health had prevented them from seeking a timely appeal.

Lawyers felt that it had become harder to win cases in the CACD, with fewer grants of leave being given, tougher criteria for appeals out of time and fresh evidence rules being too stringent. Because of this, advocates found appellate work frustrating and felt the fundamental objective of the CACD’s attitude was to dissuade appellants from seeking to appeal. The lack of funding, particularly for initial work on appeals created a further lack of incentive for lawyers to take on appeals

The findings of this research beg the question: What use is an appeal system that people cannot access? This report raises serious questions about whether the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) is a legal body capable of righting wrongs done to women by the criminal justice system.

Women who have been unfairly sentenced or wrongfully convicted deserve access to justice. We cannot allow them to languish in prison with no hope of redress.

Naima Sakande is the Women’s Justice Advocate at APPEAL.

The 1 page abstract of the paper can be read here, the brief executive summary here, and the full paper, complete with recommendations for reform, is here.