The months of March and April felt like an eternity as the world was changed by COVID-19, and justice authorities grappled with how to deal with the issues in prisons.

Time was of the essence. Almost a quarter of Scottish prison staff were absent from work. Men in Barlinnie described life inside in lockdown, with their families and the virus on their minds:

You know sometimes when you take your jumper off, you get sparks and static, and the hair on your skin stands up. Well that’s how it feels here sometimes, only in here it can be like there’s live electricity in the air. I was thinking that if someone switched the lights on with a big switch, this place could go on fire.

Not sure how to describe how it is here, it’s weird and quiet but stressful as well. The screws look tired and stressed as well. They must be worried about their families as well…

Pressured times call for emergency measures. A range of people called for early release: criminologists, lawyers, charities and collectives, including Howard League Scotland and Scottish Prisoner Advocacy & Research Collective, families of prisoners, Scottish Human Rights Commission, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, as well as a spokesperson for the Prison Officers Association.

For context, seven individuals (0.1 per cent of the prison population) are self-isolating at the time of writing. However, that figure had peaked as high as 125 self-isolating in late March and 105 in late April. Sadly, six prisoners and one prison officer have died from suspected COVID-19-related causes.

Political Consensus

In the Scottish Parliament, there was cross-party support for the Coronavirus (Scotland) Act 2020, authorising emergency powers for early release. Based on this, the Release of Prisoners (Coronavirus) (Scotland) Regulations 2020 were backed by members of the Scottish National Party, Labour, Greens and Lib Dems, and the Tories chose to abstain rather than oppose it.

There is clear evidence from the dialogue that the Scottish Prison Service has had with public health officials that to increase single occupancy of cells—rather than the double occupancy that we have in our overcrowded prisons—would help us to contain the virus... I believe the [early release] measures to be right and proportionate, and I am pleased that, broadly, they have support around the chamber.

Cabinet Secretary for Justice Humza Yousaf MSP.

Comments by Scottish politicians suggest in-depth discussion and consensus building behind the scenes. There has been publicly accessible scrutiny of the Scottish Government and Scottish Prison Service by the Parliament, Justice Committee and COVID-19 Committee.

Once the regulations were in place on 4 May, the approach taken by Scottish authorities differed from the havering and prevarication of authorities in England and Wales, who announced an early release scheme, putatively for thousands, on 4 April, but have since hardly implemented it. One government rushed to say they would, but didn’t, and one government didn’t rush, but did what they said they would.

Implementation of early release scheme

The scope of the scheme in Scotland:

- Eligibility: People serving a short sentence of less than 18 months, who have three months (90 days) or less until their release date;

- Exclusions: People who have committed certain offences (sexual, terrorism, COVID-19-related, domestic abuse) or subject to a non-harassment order are ineligible.

Those approved for this scheme are released from prison unconditionally (not out on licence), without an electronic monitoring tag. Release is risk assessed, and falls within the victim notification scheme.

According to the Scottish Prison Service, of the 445 people who met the eligibility criteria, a total of 348 people were released from prison early during May 2020. That is 314 men and 34 women, the vast majority of whom are aged under 47 years old. A discretionary veto by prison governors prevented the early release of 63 people. A further 34 eligible people were instead released by ‘other’ means.

It's too early yet to speculate on how those released early have fared or what impact the scheme may have had. The volume of hard work (from home) by charities and local authorities in supporting resettlement deserves more recognition than it has received. During the pandemic, the Wise Group and partners have seen a three-fold increase in people accessing post-release support and they have given out ‘liberation packs’, offering mentoring and things like supermarket vouchers for mobile phones.

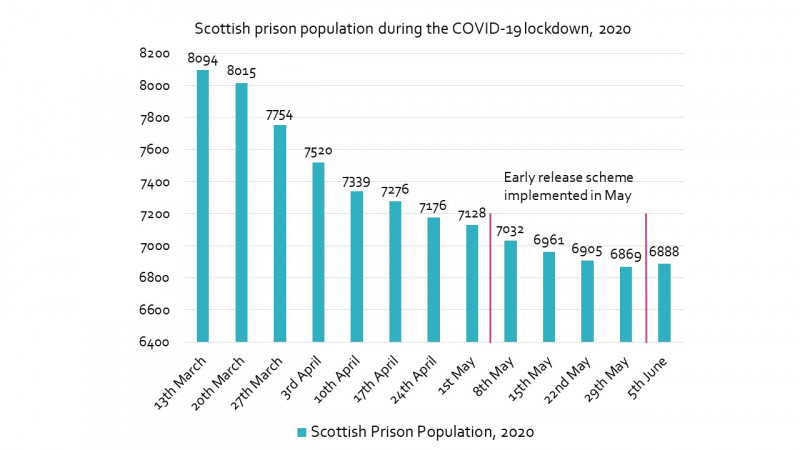

In the 12 weeks from 13 March to 5 June 2020, the Scottish prison population decreased by approximately 15 per cent. Concurrent with the early release scheme, normal liberations have continued with an estimated 100-150 people released a week. Meanwhile, numbers of people remanded in custody are relatively high (1,408 on 5 June), making up 20 per cent of the prison population.

This overall picture illustrates how, as others have noted, the ‘front door’ of the courts and Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service have more influence on prison populations than ‘back door’ measures such as this early release scheme. Our prison population may rise and revert to pre-pandemic levels as courts start back up.

Early release is very welcome. More now needs to be done to pursue decarceration if we are to realise long-held hopes of re-thinking punishment and imprisoning far fewer of our own people. Time is still very much of the essence.