Last time I talked about how we have seen significant improvements in outcomes in primary and secondary education for pupils from ethnic minority backgrounds.

However, I also showed how black pupils in particular still face discrimination in the school system.

In this piece I will sketch out what post-16 education looks like for people from different ethnic groups, still maintaining a focus on black students.

Why is post-16 education important?

Staying on to complete further and higher education increases a person's chances of gaining employment and potentially increases their earnings. Within this overall trend, however, there are differences in outcomes according to the particularities of post-16 education completed.

The type of further education institution attended, of qualifications gained for entry into higher education, of university attended and overall degree classification achieved, all affect the relative gains from post-16 education. Ethnic minority students face disadvantages in all of these aspects of education.

The picture of post-16 education for ethnic minorities

Inequalities between different ethnic groups are visible after young people complete their GCSEs. Students from ethnic minorities are far more likely to continue their education at further education colleges, which tend to offer vocational qualifications, than at school sixth forms, which offer A levels. This means that students from all ethnic minority groups other than Indian and Chinese are more likely to pursue alternative, lower entry routes into higher education.

This is particularly the case for students from black ethnic groupings, of which 65% pursue qualifications other than A levels as a way of entering higher education, compared to an everage of 35% across all ethnic groups.

This has an effect on the type of universities students attend, with higher tariff institutions biased towards traditional applicants applying with A levels directly from school. Some large employers have also been shown to have a preference for traditional post-16 qualifications.

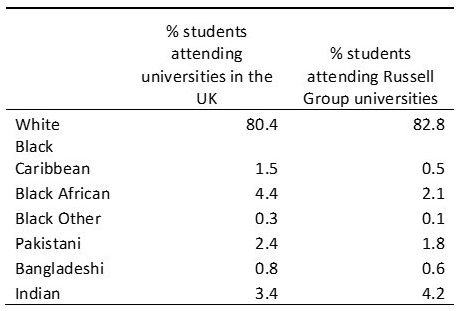

Patterns in the types of universities attended by different ethnic groups can be partly explained by the issues outlined above. As you can see from the adjacent table, people from minority ethnic groups, especially Black groups, are under-represented in Russell Group universities. The overall representation of black students in Russell Group universities is very low, with only 8% attending these institutions, compared to 24% of all white people.

Patterns in the types of universities attended by different ethnic groups can be partly explained by the issues outlined above. As you can see from the adjacent table, people from minority ethnic groups, especially Black groups, are under-represented in Russell Group universities. The overall representation of black students in Russell Group universities is very low, with only 8% attending these institutions, compared to 24% of all white people.

Black and minority ethnic students therefore become concentrated in post-1992 universities and former polytechnics, with 44% of all Black, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian graduates coming from these institutions compared to 34% of other ethnic groups. In fact, students from all ethnic groups except Chinese are more likely to attend newer, lower tariff universities compared to white people. There are also differences in participation rates, with only half the proportion of Black Caribbean and Bangladeshi students attending university, compared to Indian and Black African students.

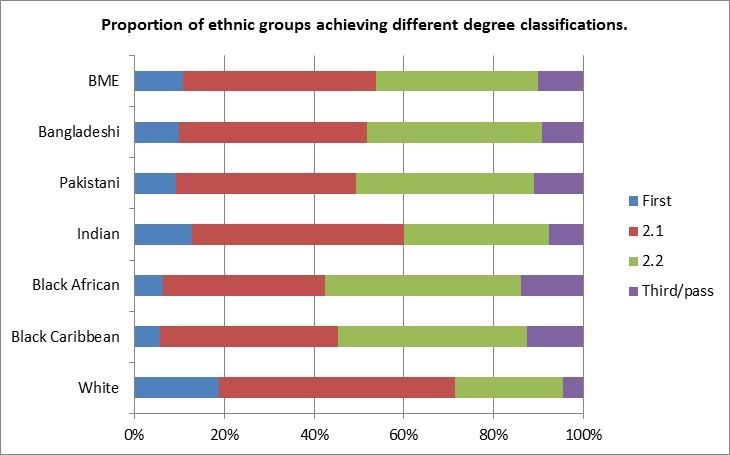

The type of qualification gained for entry into higher education has an effect on attainment at university, whereby students with A levels gain higher final degree classifications than those with vocational qualifications. This means that the negative effects of ethnic minority students entering higher education via alternative routes are compounded by the fact that they are more likely to achieve a lower degree classification.

As you can see from the adjacent graph, 71.5% of white students gain a 1st or 2.1, compared to 53.8% of all black and minority ethnic students, and 43.2% of black students. A greater number of lower seconds are awarded to students from black ethnic groups than upper seconds.

At first glance it seems that simply increasing participation in post-16 education will improve outcomes for ethnic minority graduates and reduce inequalities between ethnic groups. A more nuanced analysis suggests that further and higher education are structured in such a way as to reproduce inequality and disadvantage for ethnic minorities. As we shall see next time, this combines with discrimination in the labour market to adversely affect employment outcomes.