To 1945, 1979 and 1997 might be added 2019: a pivotal General Election with the potential to reshape policy and politics in the UK for a generation.

In the case of criminal justice, we should expect a resumption of the kind of criminal justice growth and expansion last seen under the Labour governments between 1997 and 2010, an expansion that, temporarily at least, the coalition and Conservative governments between 2010 and 2019 successfully halted.

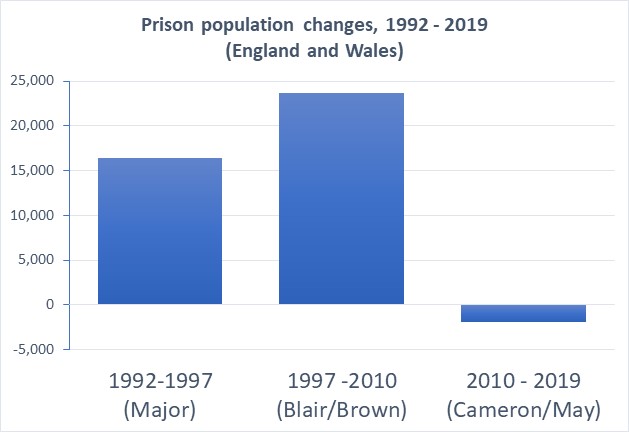

When Labour came to office in 1997, it inherited a prison system that John Major’s outgoing Conservative administration had greatly expanded. The three Blair/Brown governments between 1997 and 2010 built on this legacy, expanding the system further. Over the course of a generation between 1992 and 2010, the prison population in England and Wales nearly doubled, from just under 45,000 in 1992 to nearly 85,000 in 2010.

Had this trend continued between 2010 and 2019, the prison population in England and Wales would now stand at around 103,000. In fact, last Friday, the morning after the General Election, it stood at 83,376, slightly lower, in fact, than it had been in 2010.

The dangerous and disgusting conditions far too many prisoners and prison officers across England and Wales are currently being forced to live and work in are, quite rightly, regularly condemned. Less discussed is the successful prevention of further prison growth under the coalition and Conservative governments.

These governments did little to reverse the obscene expansion under the Major, Blair and Brown governments. They can, though, take some credit for not compounding the harm by expanding the system further.

This success now looks set to be disavowed, with plans by Boris Johnson’s government to build 10,000 new prison places, while also keeping open those dilapidated old Victorian prisons the Cameron and May governments had planned to close. After a decade of no prison growth, the new government looks set to pick up where the Major, Blair and Brown governments left off.

Those familiar with the Ministry of Justice prison population projections will know that the latest projection, looking forward to 2024, estimates that the prison population will remain flat at around 81-82,000. If this is the case, why is the government planning to build 10,000 new prison places?

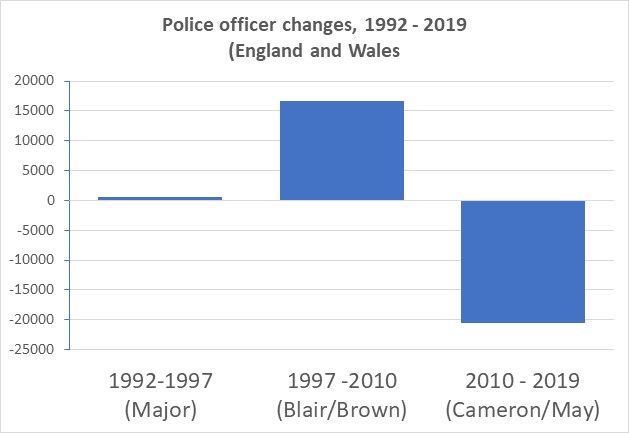

This is where the pledge to recruit 20,000 more police officers is significant. The criminal justice system is an interconnected set of institutions. Changes in one part has knock-on effects elsewhere.

The prison population grew under the Major government, despite the fact that police officer numbers remained stable. The Blair and Brown governments dramatically expanded police officer numbers, as part of its ‘tough on crime’ agenda. The coalition and Conservative governments of Cameron and May reduced police officer numbers back roughly to where they stood under Major.

There is no one-to-one correspondence between police officer numbers and prison population levels. That said, over the past decade, the number of stop and searches, arrests, prosecutions, convictions and sentences have all fallen, and to good effect. More than 3,000 children under 18, for example, were in prison at any given time in 2010. By the time of last week’s General Election, this had fallen to around 800.

A large increase in police officer numbers will likely contribute to a reversal of this trend, as the government itself admits. Giving evidence to the House of Commons Justice Committee in October, Sir Richard Heaton, the Ministry of Justice Permanent Secretary, made explicit the link between increasing police officer numbers and the government’s plan to expand prison capacity.

The other factor inflating the prison population will be the 20,000 additional police officers. It is hard to convert those into prison places because we do not know exactly what they will be doing in policing terms. Assuming that they arrest and charge people, we can expect the charge rate to go back closer to what it was in 2010. There is a very low charge rate at the moment. That is the thing driving the prison population, as well as the sentencing changes.

In its 2019 General Election manifesto, Labour committed to expanding the police force by even more than the Conservatives. Had it pulled off an unlikely victory last week, a resumption of prison and criminal justice growth was therefore likely. For all its radicalism on social and economic question, an ongoing fidelity to key aspects of New Labour’s criminal justice world view remains one of Corbynism’s guilty secrets. Only time will tell whether, under a new leader, this will change.

An expanding criminal justice footprint – including more police officers and a growing prison population – is a sign of failure. The criminal justice system all too often picks up, through arrest, prosecution and punishment, many problems that would better be prevented or resolved through our health, education, housing and social welfare systems.

There will be opportunities in the coming weeks, months and years to make the case for shrinking the criminal justice footprint and developing a more balanced and holistic set of social policies to underpin a safer society. A government overtly committed to the opposite might, paradoxically, help to clarify the issues at stake.

That said, those organisations opposing further criminal justice growth need to buckle up for what is coming down the road, and think carefully, and quickly, about how they are going to respond.