I have been asked to speak on the topic of ‘After the election: where now for social and criminal justice’. The Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, of which I am the director, is an independent public interest charity that sits between the worlds of research and policy, practice and campaigning. Our mission is to inspire enduring change by promoting understanding of social harm, the centrality of social justice and the limits of criminal justice. Our vision is of a socially just society in which everyone benefits from equality, safety, economic and social security. Criminal justice and social justice are therefore of great interest and concern to me and my colleagues.

There are a number of reference points for these questions of social and criminal justice. One of them – the big picture as it were – is the ongoing global financial upheavals and the challenge associated with the current budget deficit. The Prime Minister is today going to be giving a speech discussing the government’s plans to tackle the deficit. He is going to be telling us that ‘the overall scale of the problem is even worse’ than previously thought. That the cuts are going to have ‘enormous implications’ for ‘our whole way of life’.

Some in the coalition government see this a rare opportunity to reframe the way government operated in the UK. Speaking to the Financial Times one Treasury official put it as follows:

'Anyone who things the spending review is just about saving money is missing the point. This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to transform the way that government works.'

I find it very difficult to feel anything other than deep anxiety when I hear these kinds of statements. The Prime Minister, along with his deputy Nick Clegg, has been keen to emphasise that the pain of cuts will be shared and spread. I have no reason to doubt that they are sincere in stating this. However, we know from research on previous recessions and previous budget retrenchments that it is poor, the maginalised, those least able to defend their corner and argue their case, who suffer the most during times of austerity.

Another reference point is what I will term the social justice legacy. There are various ways that social justice can be measured and conceptualised. Here I used changes in poverty levels over recent years as a measure of social justice, or perhaps more accurately social injustice. According to the excellent Poverty Site:

- In 2007/08 13½ million people in the UK were living in households with incomes that were 60% or less of the median houshold income. This is around one fifth of the entire population.

- This is an increase of 1½ million compared with 2004/05.

- The number of those on low incomes is lower than the early 1990s, but much higher than the early 1980s, when of course we had a very deep and divisive period of recession and spending cuts.

The poorest in society are, therefore, objectively in a much worse position to survive the current recession and likely spending cuts than was the generation of the early 1980s. We are still living with the effects of that earlier, 1980s recession. This is a very worrying precedent for the coming period of economic distress and budget retrenchment.

This brings me on to the third reference point: the criminal justice legacy. During Labour’s time in office criminal justice expenditure, and the system as a whole, grew significantly. Against this background the numbers of women under criminal justice control has, predictably, grown. In 1998 21,502 women received a community sentence. This had grown to 30,809 by 2008. The comparable figures for prison were 6,567 and 8,359. In total, 288,388 women received a court sentence in 2008, compared with 235,494. This all happened, of course, during a time when the official crime rate was falling.

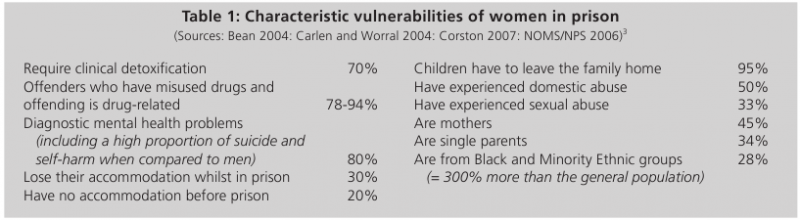

What about the kind of women who ended up in the criminal justice process, and in prison in particular? The data collated by Rachel Goldhill for an article last year in Prison Service Journal tells its own story:

As part of her landmark report into vulnerable women in the criminal justice system Baroness Jean Corston visited Brockhill prison. This is what she wrote of the experience:

'When I visited Brockhill in May I was given a list of some of the events that had happened in the preceding ten days, which I was told were fairly typical of everyday life in a women’s local prison. It is shocking.

- A woman had to be operated on as she had pushed a cross-stitch needle deep into a self-inflicted wound.

- A woman in the segregation unit with mental health problems had embarked on a dirty protest.

- A pregnant woman was taken to hospital to have early induced labour over concerns about her addicted unborn child. She went into labour knowing that the Social Services would take the baby away shortly after birth.

- A young woman with a long history of self-harm continued to open old wounds to the extent that she lost dangerous amounts of blood. She refused to engage with staff.

- A woman was remanded into custody for strangling her six-year old child. She was in a state of shock.

- A woman set fire to herself and her bedding.

- The in-reach team concluded that there was a woman who was extremely dangerous in her psychosis and had to be placed in the segregation unit for the safety of the other women until alternative arrangements could be made.

- A crack cocaine addict who displayed disturbing and paranoid behaviour (but who had not been diagnosed with any illness) was released. She refused all offers of help to be put in touch with community workers.'

It is very difficult to be anything other than outraged and disgusted that such desperately vulnerable fellow human beings are put into places of punishment.

So what is to be done? I will confine myself to three brief comments.

First, we need to support radical practice and interventions that are genuinely transformative of individuals’ lives rather than being merely amerliorative.

Second, we need to invest in critical research and analysis of current and emerging trends. This is important not as a quaint intellectual or academic practice. It is important because is often necessary to understand the world if one is to go about changing it.

Third, we need to start seeing women who are subject to criminal justice control as people and individuals with a past, a present and a future; as individuals with needs and right to be treated with dignity and respect; as women with friends and families, who have dreams and aspirations. In other words, we need to stop treating them as ‘offenders’ to be managed; whose ‘offending behaviour’ needs to be addressed. For it is only because women subject to criminal justice control are treated as a criminal ‘other’ that the barbaric set of policies that characterise current policy approaches are able to be justified.