This article utilises a social harm perspective to expose young people’s vulnerabilities to crime and to connect these to their experience of wider social harms. This necessarily involves identifying harms which result from structural forces and institutional policies, as well as from cultural practices which impact on young people’s self-worth, respect, and recognition. The focus of the article is comparative, focusing on young people’s experience of social harm across five European countries. The article aims to provide an antidote to the prevailing social and political representation of young people and crime – which certainly exists in Britain – which projects them predominantly as perpetrators of criminal harm.

Defining and operationalising social harm

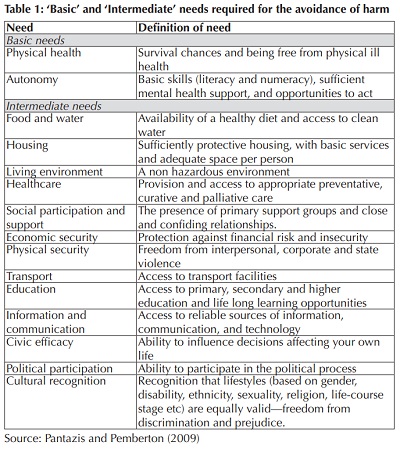

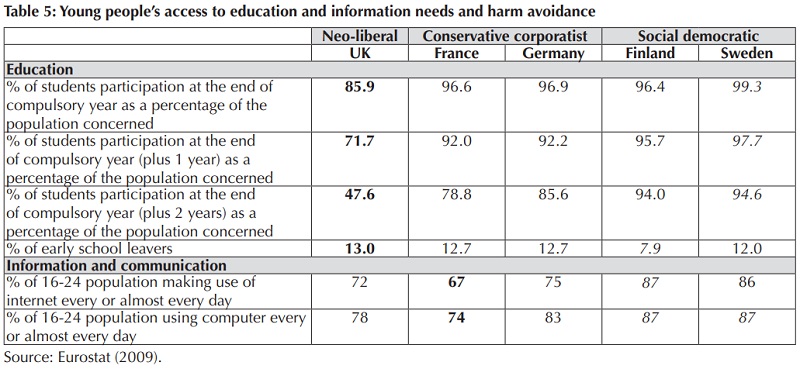

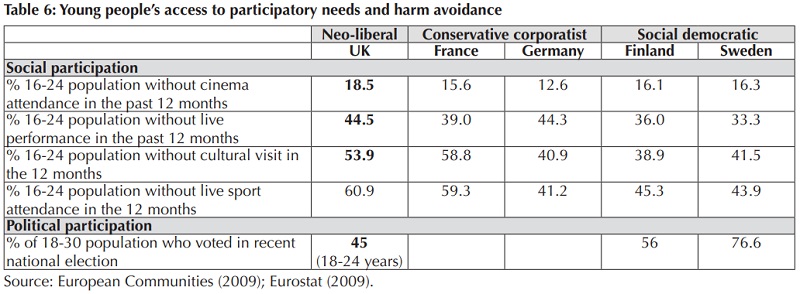

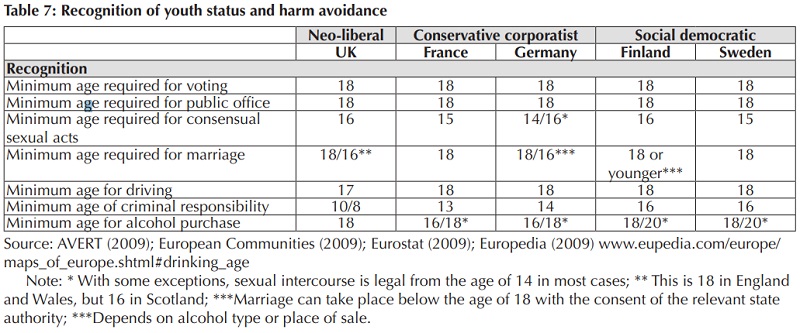

Defining harm, like crime, is fraught with difficulties. However, unlike crime the concept of harm is not intimately connected with processes of legality and intent. Instead it is concerned with outcomes – detrimental outcomes to human well-being. The article utilises the normative approach taken by Pantazis and Pemberton (2009) that drew upon Doyal and Gough’s (1991) theory of human need. According to Doyal and Gough ‘basic human needs, … stipulate what persons must achieve if they are to avoid sustained and serious harms’. At the most basic level individuals require physical health and autonomy, however, in order for these two ‘basic’ needs to be met a further tier of need fulfilment is required which Doyal and Gough term as ‘intermediate needs’. These include food and water; housing; work; physical environment; healthcare; support networks; economic security; physical security; education; birth control and childbearing. Pantazis and Pemberton (2009) sought to extend this list of intermediate needs to include information and communication; transport; political participation; civic efficacy; and ‘recognition’, and also excluded categories of need relating to specific populations. These categories of need are sufficiently broad enough to facilitate a consideration of age-specific social indicators, allowing for a comparison of the experiences of young people in different European countries (Table 1). For the purposes of this paper, age-appropriate indicators were sought from a number of international and regional organisations including the World Health Organization (WHO), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and Eurostat although age-specific indicators were unavailable for some needs including transport and healthcare (Tables 2 to 7). For each social indicator, countries with the highest need fulfilment are highlighted in italics and those with the lowest are highlighted in bold.

Young people’s experience of social harm

This section describes young people’s experience of harm in five different European countries. In order to explain young people’s experiences, the countries have been selected to represent different welfare regime based on the political economy approach developed by Cavadino and Dignan (2006):

- Neo-liberal states epitomise political conservatism and economic liberalism and are characterised by a strong free market and a minimal or residual welfare state with a prominence on means testing. The dominant penal ideology rests heavily on a law and order agenda with an emphasis on exclusionary punishment methods involving the use of prison.

- Conservative corporatist states emphasise reciprocity—insurance based benefits exist as social rights but there are obligations on the part of benefit recipients in terms of their familial and employment responsibilities. The dominant penal ideology is one of rehabilitation, using a variety of penal sanctions including moderate use of imprisonment and diversionary strategies for young offenders.

- Social-democratic states offer generous welfare support with benefits graduated according to earnings, which means that temporary interruptions from the labour market do not have deleterious impacts on living standards. Penal welfarism is dominant: the prevention of crime is promoted through a benevolent welfare system and active employment policies and an egalitarian ethos and its emphasis on collective (rather than just individual) responsibility contributes to relatively low levels of imprisonment.

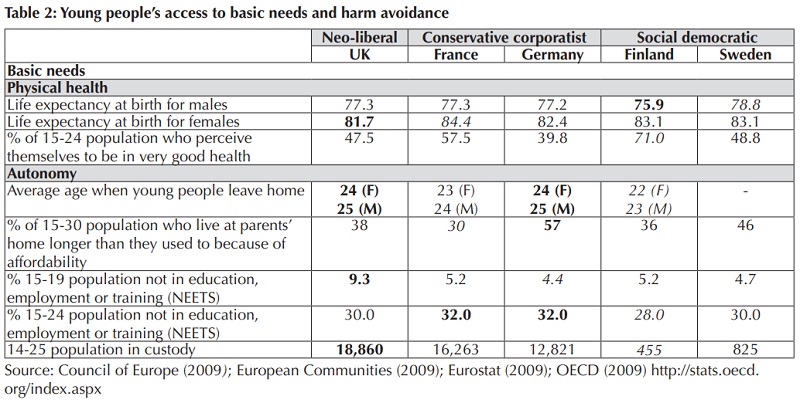

Looking at the fulfilment of basic needs, in all types of society today’s young people can expect to have a life expectancy which is far longer than previous generations—although it is lowest in the UK (for women) and Finland (for men) and highest in France (for women) and Sweden (for men). However, only in Finland do the vast majority of young people report to having very good health (71 per cent). Fewer than half of all young people in the UK, Germany, and Sweden report very good health.

Autonomy captures a number of elements but crucially for young people is their ability to leave the parental home and to live independently. The median age of leaving home is highest in the UK and Germany and lowest in Finland. German youth are especially likely to identify affordability as a reason for delaying moving out. Autonomy also reflects opportunities to be involved in purposeful activity such as employment, education, or training. Overall, nearly 40 per cent of Europeans aged 15-24 are lacking such opportunities although rates are around 30 per cent for young people in the five countries considered here. However, risks were more differentiated in relation to the younger age group (15-19), affecting one in ten young people in the UK— the highest proportion of all countries. The ultimate test of autonomy is young people’s deprivation of liberty. The UK has the highest numbers of young people in penal establishments; Finland and Sweden have the lowest numbers. Once population size has been accounted for, it is very likely that differential criminal justice responses explain these disparities in young people’s autonomy.

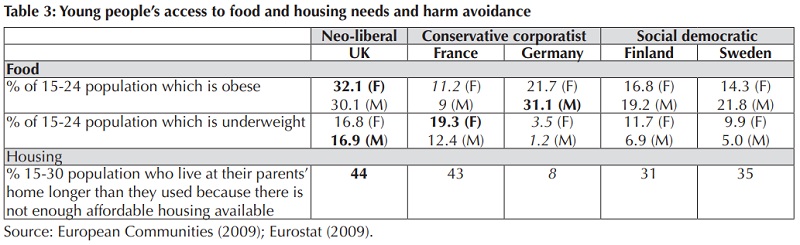

For these two basic needs to be met a number of intermediate needs are required. In examining needs relating to food, young people in the UK emerge as particularly deficient in terms of their access to a healthy diet. Nearly one in three young people living in the UK (and also one in three German young men) are obese. Obesity rates are lowest among French youth although the problem of underweight is highest among young French women (19 per cent). UK young men and women follow closely behind, at 17 per cent. Housing needs are also particularly acute for young people living UK with 44 per cent reporting that young people live at their parents’ home longer than they used to because of the shortage of affordable housing.

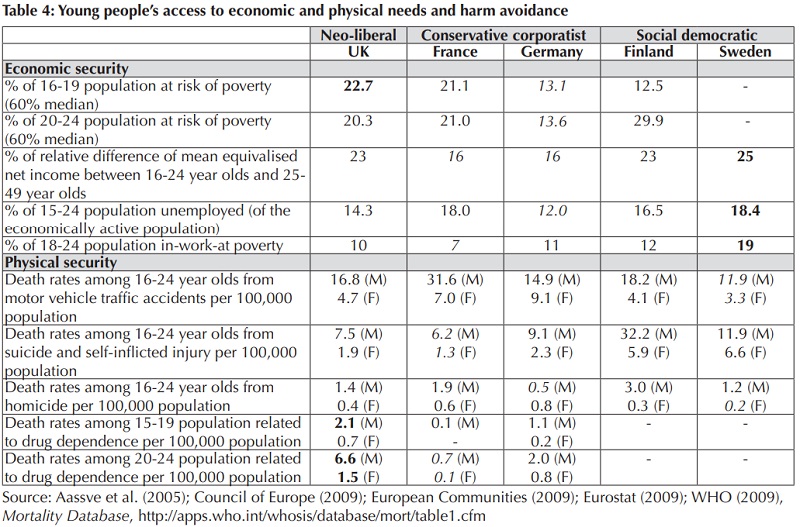

Significant proportions of young people living in Europe experience economic insecurity. The risk of income poverty is especially high among UK and French young people aged 16 to 19 years. However, for young people aged 20-24, youth poverty risks are significantly higher in Finland. Economic insecurity across a number of other dimensions including income differentials between young people and the population aged 25-49, unemployment and also in-work poverty rates are highest in Sweden. The high rate of youth poverty in the two Scandinavian countries is especially significant in the context of their exceptionally low overall poverty rates but may be explained in terms of young people leaving the parental home at a very early age (Aassve et al., 2005).

Young people’s precariousness in terms of physical security is also shown, especially for men. Among young people in UK, France, and Germany the leading cause of death is motor vehicle traffic accidents, followed by suicide and self-inflicted injury. In Finland and Sweden it is the reverse and this pattern is stable across the gender divide. Homicide rates are exceptionally low across all five European countries but the small numbers mean that it is difficult to decipher patterns between them. On the other hand death rates related to drug dependence for the three countries for which data exist indicate that the UK has the highest rates, particularly among 20-24 year olds.

In most European countries, compulsory education ends between 14 and 17 years of age although many young people choose to continue with their studies rather than enter the labour force. However not all young people complete their compulsory education. In the UK only 86 per cent of 16 year olds are still in compulsory education and only 50 per cent of young people are in education two years after the end of compulsory schooling. These are the lowest rates across the five countries considered. Young people in Finland and Sweden have the highest participation rates in education, and they are also more likely to have daily internet and computer access.

UK youth also have restricted participation in a range of social activities and involvement in formal politics. For example, in the previous 12 months 19 per cent did not visit the cinema, 45 per cent did not attend a live performance, 54 per cent did not attend a cultural event, and 61 per cent did not see any live sport. Participation in these activities is highest among German youth, followed by young people in Sweden and Finland.

Recognition of lifestyle based on a range of factors, including age, is a fundamental pre-requisite for human need and well-being. For young people it captures a number of diverse elements including their involvement in intimate relationships, their ability to influence the political process, their ability to purchase and consume goods and services, as well as their culpability for crimes. This is where the most significant difference can be found between the five countries; children as young as ten in England and Wales and eight in Scotland are considered criminally responsible. Yet, in Sweden and Finland the age of criminal responsibility is 15.

Explaining young people’s experience of social harm

Humans need fulfilment and harm avoidance among young Europeans is differentially experienced. The UK, with its neo-liberal punitive/welfare arrangement, places young people in a precarious existence. Welfare reforms over the last 30 years have restricted benefit entitlement for the majority of very young people who find themselves out of work and cut benefit levels for others—increasing young people’s dependence on their parents and reducing opportunities for independent living. At the same time, the government has sought to turn young people into active citizens by compelling them to take up work or training after a period on benefits—even if this entails them taking up poorly paid and unskilled work. Moreover, young people are considered equally culpable as adults for the criminal harms they commit and this helps to explain why the UK imprisons more young people than the other four countries considered. Despite the obsessive focus on crime, the main source of physical harm for young people is the motor vehicle. Young people are 12 times more likely to be killed in a motor vehicle accident rather than be murdered.

Conservative corporate and social democratic states perform much better in terms of young peoples’ needs fulfilment. This is especially the case for Finland and Sweden where the exceptionally low numbers of young people imprisoned signifies young people’s autonomy and the states commitment to respond in ‘social’ ways rather ‘penal’ ways to young people’s involvement in criminal harm. A comprehensive welfare system ensures that young people living in Finland and Sweden have their needs fulfilled in relation to a number of key areas. However, young people’s exceptionally high poverty risks are striking. Youth, as a transitionary phase, seems to place young people in Finland and Sweden in an especially precarious situation. A short spell of life in poverty appears to reflect the ‘price’ that young people pay for their independence and also their decision to continue with their studies. In this regard, Germany’s record is stronger. Young German youth benefit from relatively high education and employment opportunities and also have lower risks of poverty—although the imprisonment of young people remains high.

Christina Pantazis is Senior Lecturer and Head of the Centre for the Study of Poverty and Social Justice at Bristol University.

References

Aassve, A., Iacovou, M., and Mencarini, L. (2005), Youth Poverty in Europe: What Do We Know?, ISER Working Papers, 2005-2.

AVERT (2009), www.avert.org/age-ofconsent.htm

Cavadino, M. & Dignan, J. (2006), Penal Systems: A Comparative Approach, London: Sage.

Council of Europe (2009), Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics—SPACE 1—2007, Council of Europe Switzerland.

Doyal, L. and Gough, I. (1991), A Theory of Human Need, London: Macmillan.

European Communities (2009), EU Youth Report, European Communities: Belgium.

Eurostat (2009), Youth in Europe: A Statistical Focus, Eurostat: Luxembourg.

Pantazis, C. and Pemberton, S. (2009), ‘Nation states and the production of social harm: Resisting the hegemony of TINA’, in Coleman, R., Sim, J., Tombs, S. and Whyte, D., eds. State, Power and Crime, London: Sage.