The introduction of the Community Order (CO) and Suspended Sentence Order (SSO) in the 2003 Criminal Justice Act, on paper at least, radically reconfigured community sentences in England and Wales. The CO replaced the range of community sentences previously available with a single sentence. The SSO brought in a custodial sentence to be served in the community unless breached. Both orders were to be made up of one or more requirements from a possible of 12 (including unpaid work, supervision, accredited programmes, curfew and drug treatment).

Since the orders were implemented in 2005, the Community sentences project at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies has been monitoring the use and impact of these two new orders through analysing official data and engaging with sentencers, probation staff and those subject to the orders. This has been the first consideration of how those affected by the orders perceived and use them and what difference these new arrangements have made. Overall, although well-received by sentencers and probation staff the project has found the orders have failed to achieve their intended aims, namely to:

- reduce the use of short-term custody;

- tackle uptariffing;

- tailor community sentences to individual offender need.

Having recently completed the seventh and final publication in this series, this article highlights some of the key findings of the most recent research report, before questioning whether the ambitious intended aims outlined above require more radical changes than those introduced in the 2003 Criminal Justice Act.

The orders’ impact on short-term custody

It is impossible to say with certainty how far diversion from custody has been achieved by the CO and SSO, but all the evidence suggests that it is very little. The orders’ impact would, one expects, be most discernable between 2006 and 2007. In these years, despite some reduction in the use of custodial sentences of six months or less, there was no overall change in the use of custodial sentences of 12 months or less in either the magistrates’ or Crown Courts.

The SSO has been a far more popular sentence than the Home Office expected and throughout this project there has been criticism about its use. Sentencers, particularly magistrates, are considered to be very keen on the SSO. It is considered to be used as an alternative to custody, more so than the community order, but not always. Given that the overall rate of short-term custody has not reduced the popularity of the SSO has led to concerns, including from the Ministry of Justice, that rather than tackle uptariffing, the SSO may be exacerbating uptariffing, with some who would have previously received a CO now subject to a SSO (Ministry of Justice, 2008a; Ministry of Justice, 2008b; House of Commons Justice Committee, 2008).

The limited use of requirements

The notion of tailoring orders to individual offenders that the menu of 12 requirements proposed is wellliked by probation officers and sentencers. However, in practice the orders continue to look very much like their predecessors, relying on three requirements: unpaid work, supervision and accredited programmes. Half the requirements are rarely used. There are several reasons why this is the case; some theoretically available requirements are still not able to be imposed in some areas due to limited resources (the alcohol treatment requirement is a particular area of perceived unmet need in this regard), some are difficult to impose (the mental health treatment requirement), and there are reservations about what some requirements can meaningfully deliver (for example, how will prohibited activities or exclusion requirements be effectively monitored?).

Probation practice

I think we're definitely steering away from the old kind of welfare-based supervision, we're almost like a little business organisation I think now… [those on orders] go off and do unpaid work or go and do a programme and as Offender Managers or probation officers we kind of oversee it. We're almost signposting I suppose and…sometimes it's nice to get a supervision because it doesn't happen hugely anymore and it's nice to sort of do that. (Probation officer quoted in Mair and Mills, 2009)

Managing orders through the processes of partnership working, brokering service and commissioning, was, for those more experienced probation officers, a shift from their undertaking one-to-one contact with those subject to order. Such changes for the probation service are not simply the result of the introduction of the orders. The past few years have undoubtedly been a time of great change for the probation service overall – not least the introduction of NOMS, probation trusts and contestability. The division of activity through requirements supports a framework where probation officers are the overseers rather than necessarily the delivers, of community-based sentences.

Such a change not only has consequences for the probation service, but also for those subject to orders. Those undertaking COs or SSOs we interviewed suggested the individual probation officer and the relationship between probationer and probation officer makes a substantial difference to how helpful the order is. Several interviewees said they chose to take part in this research because of a sense of personal obligation to their probation officer. Probation officers considered less contact between themselves and those on orders could have significant implications in terms of building trust and effectively encouraging compliance – if as one probation officer said, the first time an offender hears from them is their signature at the end of a breach warning letter.

Yes, but are they tough enough?

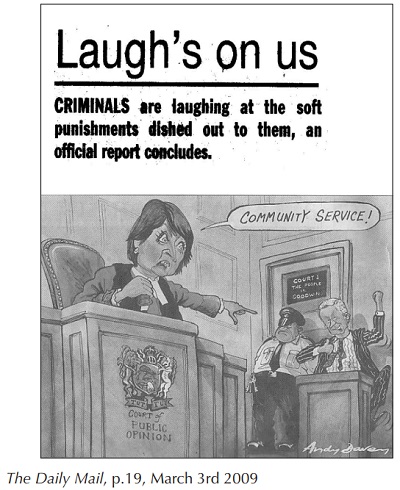

Much of the media coverage of Three years on focused on a quote from one probation officer – used as evidence community sentences are a soft option (see below).

Such coverage – readers will not be surprised to hear – does not reflect the findings or conclusion of our research. Perhaps some readers would dismiss such headlines with a sigh about tabloid-media sensationalism. However, it is not simply the media who frame community sentences as fundamentally delivering punishment. Take this recent quote from the Secretary of State for Justice:

Gone are the days when the main duty of probation officers was to ‘advise, assist and befriend’ offenders. ‘The reform and rehabilitation of offenders’ remains one of the purposes of sentencing under section 142 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003, but it is only one of a number, first among which is ‘the punishment of offenders’. (Jack Straw, February 2009, speech to trainee probation officers)

During this project the terms of the debate about community sentences have been largely situated in the extent to which they are onerous, ever more robust and rigorous enforced. This narrow focus on punishment continues to overshadow the potential for a more informed public dialogue about what we think community sentences can realistically achieve.

A false dawn?

In everyday practice there's not a lot of change between how it was [before the orders] and how it is now. (Probation officer, quoted in Mair and Mills, 2009)

Reflecting on the findings of the Community sentences project overall, we do not think the orders’ failure to meet their hoped-for aims is fundamentally due to those working within the criminal justice system not taking advantage of the opportunity the introduction of the CO and SSO provided. The provisions in the 2003 Act streamlined the available community sentences. On their own it is unsurprising the orders have led to relatively little change in the use of short-term custody, uptariffing or tailoring community sentences to individual offender needs. Rather, these aims were always far more ambitious than a modest reconfiguration of community sentences could reasonably be expected to deliver.

Helen Mills is Research Associate at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies.

To download this report or for more details about previous publications in the Community Sentences series visit: https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/tags/community-sentences-project-pub….

The Community Sentences Project was funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation.

References

House of Commons Justice Committee 2008 Towards Effective Sentencing. First report of session, 2007–08 1 , London : The Stationary Office.

Mair, G. and Mills, H. 2009. The Community Order and Suspended Sentence Order Three Years on: The Views and Experiences of Probation Officers and Offenders, London: Centre for Crime and Justice Studies.

Ministry of Justice 2008a Offender Management Caseload Statistics 2007, London: Ministry of Justice.

Ministry of Justice 2008b Sentencing Statistics 2007, England and Wales London: Ministry of Justice.

Straw, Jack 2009 Transcript of speech by Jack Straw to trainee probation officers at the Probation Study School, University of Portsmouth, 4th February. Probation and Community Punishment. Available at www.justice.gov.uk/news/sp040209.htm (accessed 3 June 2009).