Youth justice has become an increasingly important part of the criminal justice system, and has faced a range of challenges in the last few years. Practice within the youth justice system has been developed significantly, with important roles being played locally by youth offending teams (YOTs) and custodial establishments, and centrally by the Youth Justice Board (YJB).The government could certainly not be accused of lacking legislative zeal in the field of youth justice. Yet recent legislation and published critiques have again raised questions about the actual rationale, and indeed purpose, of youth justice, questions that illustrate the conflict between the science and the politics of risk assessment.

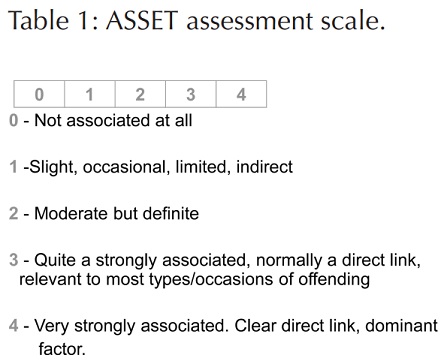

In April 2000 ASSET was introduced as a structured needs and assessment tool for use with all young offenders (10–17 years) in England and Wales – it is the key tool used in youth justice risk assessment at all its different stages. It takes the form of a questionnaire which is designed to assess risk factors for the young person in 12 psychological domains, including assessing why the young person offended, their family and lifestyle circumstances, and whether they have specific mental health or drug and alcohol related problems, in addition to issues in relation to education training and, if appropriate, employment. The form has a dual purpose, in order to assess risks that young offenders might pose to themselves, or others, as well as more general areas to consider concerning risk of reoffending. YOT workers must make a quantitative judgment on a five point scale about the extent to which they feel the risk factors in each specific domain as a whole are associated with the likelihood of further offending (see Table 1).

November 2009 saw the government’s new youth community sentencing structure come into force. The new Youth Rehabilitation Order (YRO), it is argued, will offer sentencers greater flexibility. Alongside the YRO the YJB has developed a new model of working for youth justice practitioners. This is the ‘Scaled Approach’ which purports to match the intensity of a YOTs’ work with a young person’s assessed likelihood of reoffending and risk of serious harm to others. The Scaled Approach is fundamentally dependent on the ASSET Core Profile and the intensity and duration of a young person’s YRO depends on their ASSET score. The YJB has also revised the National Standards for Youth Justice Services (YJB, 2009a) and developed new Case Management Guidance (YJB, 2009b) and practice guidance on the youth justice provisions within the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008.These, in conjunction with revised core documents for YOTs (the Key Elements of Effective Practice) underpin the ‘Scaled Approach’ and the YRO. This is the culmination of the YJB moves to structure the youth justice system around risk, risk assessment and risk-based interventions.

The use of ASSET places ‘offending and risk’ together in a negative way, risk as well as offending being seen as a negative factor, and in doing this aligns social work practice to these areas. ‘Risk’ the idea of people ‘at risk’ and those who ‘pose a risk’ have been brought to the forefront of policy. We live in a risk society and much is based on the calculation of risk. When we talk of risk in this sense the narrative used is one of protection, monitoring, containing and sustaining, this language chimes with the language used in terms of youth justice. Risk has long been associated with adolescents. The ‘problematisation of youth’ and the criminal justice and social policy response to this has been based within the parameters of risk and now this is being used to increase regulation and control, and this interpretation of risky behaviour is being carried out without exploring this notion of risk behaviour. ‘Risk’ is not only about the risks that a young person might take but is also about the risks that they are exposed to. Although the transitional state of youth in itself is a time full of ‘risk’, internally and externally, for psychologists this ‘risk’ is part of normal development and ‘risks ‘are seen to have positive consequences as well as negative and seen as part of the developmental process. But this transitional period in itself is a problem in terms of ‘risk’, in that in the discussion of ‘risk’ it is presumed there is a rational actor, the ‘prudential human’ who is rational and will make normative choices if given the correct information; but young people are often characterised as irrational and as taking imprudent decisions. This idea of irrational and imprudent is only reinforced by the demonisation of youth that is perpetrated through policy and the media.

However, YOTs currently work within a system that is consumed by ‘risk’ and determined around risk factors. This approach, generally termed the risk factors prevention paradigm (RFPP), is the dominant discourse in youth justice. However, recent work has questioned its validity. As the proponents of RFPP claim that it is scientific and built on a solid evidence base, challenges to its validity are serious, not only for the paradigm but for everything built upon it.

Case and Haines (2009) challenge the theoretical and methodological validity of the Risk Factor Research (RFR) and therefore RFPP (see also Sutherland, 2009 and O’Mahony, 2009).They show how RFR, which underpins ASSET, fails to provide solid evidence about risk and its relationship to offending. The RFR that the RFPP is based upon is founded in developmental risk factors and is deterministic in its nature, therefore creating a notion of causal risk factors. Policy makers have failed to critically analyse RFR in their creation of tools such as ASSET and in doing so have failed to account for the definitional ambiguities, inherent psychosocial bias, and inappropriate application of RFR findings.

Instead they have turned it into scientific fact and translated findings into managerialistic targets. This has created a methodological fallacy in that the risk factors identified are not necessarily causes or predictors and lack any explanatory function. The risk factors tell us little about the hows and whys young people behave the way they do. Although RFR creates interpretable results, these results are based on loose definitions and imprecise measures that at best can lead to tentative causal inferences.

The reductionist nature of ASSET and the scaled approach classifies young people creating problems in relation to the labelling of young people along with problems in terms of rights. Young people are in a weak political position to resist this classification that originates from the risk factors identified in ASSET and are linked with moral overtones of political rhetoric. Despite the claim of ‘targeted interventions’ the reductionist nature and the RFR base has scant regard to due process and actual illegal behaviour, instead interventions may contravene the privacy, liberty, and rights of a young person. Overall, the nature of risk focused practice serves to widen the net of influence exerted by the state and youth justice system.

It thus seems that the government have adopted a model that works to their advantage in two ways. Firstly, it disregards the wider socio-economic problems of our society as they are not considered ‘modifiable’, thereby detracting attention away from state culpability. This means, that because the YJB (2005) claim that wider socio-economic factors cannot be changed at a local level, then interventions targeting these problems would fail. Secondly, it disguises intrusive and controlling interventions under the rhetoric of care and support for the family, the ‘family’ being the more readily modifiable factor in comparison to national poverty. Therefore, by focusing on ‘modifiable’ risk factors, interventions are ‘likely to weigh most heavily upon those children and families living in the most challenging material circumstances’ (Jamieson, 2005, p.186). In summary, the adoption of a RFPP is inherently flawed, as it takes such an individualised view of youth offending. As programmes of intervention are built around localised data regarding risk factors, it would appear that these fundamental wider societal problems are not being addressed.

This is further evidence, if such a thing were needed, of the political nature of youth justice. The new focus on ‘risk’ is simply a device aimed at winning elections. Electoral anxiety is the motor force of the youth justice, as opposed to a considered and compassionate response to children in trouble. The politicisation of youth crime and justice has essentially served to demonise the young and institutionalise intolerance within society. Youth justice needs to become a far less political issue and needs to move beyond the notion of ‘popular punitiveness’ which many politicians have embraced in an attempt to sound tough and capable of dealing with the crime problem. Youth crime is essentially a political issue and very much regarded as an election-winner for politicians who consequently tend to discuss youth crime issues in less than rational terms, and deliberately avoid discussing anything that may lead to them being labelled as soft on crime by the opposition.

Our understanding of the relationship between risk and the behaviour of young people is lacking in many regards. To base our entire youth justice system upon such a premise shows scant regard to the young people who are caught in the system and a disregard by policy makers to actual evidence surrounding young people and offending.

Dr Ian Paylor is the Head of Department of Applied Social Science at Lancaster University.

References

Case, S. and Haines, K. (2009), Understanding Youth Offending: Risk factor research, policy and practice, Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Jamieson, J. (2005), ‘New Labour, youth justice and the question of ‘respect’, Youth Justice, 5(3), pp.180-193.

O’Mahony, P. (2009), ‘The risk factors prevention paradigm and the causes of youth crime: A deceptively useful analysis?’, Youth Justice, 9(2), pp.99-114.

Sutherland, A. (2009), ‘The “Scaled Approach” in youth justice: Fools rush in…’, Youth Justice, 9(1), pp.44-60.

Youth Justice Board (2005), Risk and Protective Factors.

Youth Justice Board (2009a), National Standards for Youth Justice Services (Draft).

Youth Justice Board (2009b), Case Management Guidance (Draft).