Recent years have seen greater criminological, legislative, and judicial attention being given to the rights of the environment, and to the rights of certain species of non-human animals to live free from human abuse, torture, and degradation (Beirne and South, 2007 ). This reflects the efforts of both eco-rights activists (e.g. conservationists) and animal-rights activists (e.g. animal liberation movements) in changing perceptions, and laws, in regards to the natural environment and non-human species. It also reflects the growing recognition that centuries of industrialisation and global exploitation of resources are (now rapidly) transforming the very basis of world ecology – global warming threatens us all, regardless of where we live or our specific socioeconomic situation.

Green criminology occupies that space between the old, traditional concerns of criminology (with its fixation on working class criminality and conventional street crimes) and the vision of an egalitarian, ecologically sustainable future (where the concern is with ecological citizenship, precautionary social practices and intergenerational and intra-generational equity). Differences in the conceptualisations of environmental harms reflect to some degree differences in social position and lived experience (i.e. issues of class, gender, indigeneity, ethnicity, and age). They are also mired in quite radically different paradigmatic understandings of ‘nature’ and ‘human interests’ (i.e. business, science, humanities, aesthetics, and philosophy).

Defining environmental harm

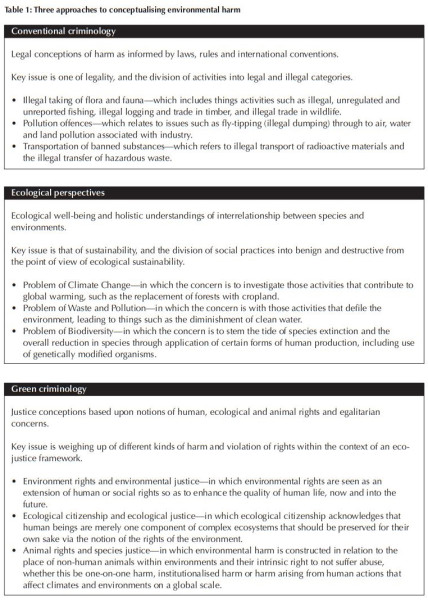

The definition of environmental harm is in fact associated with quite diverse approaches to environmental issues, stemming from different conceptual starting-points (White, 2008). These are summarised in Table 1.

Many of these harms are acknowledged as offences in both domestic legislation and via international agreements. Furthermore, the transboundary nature of environmental harm is evident in a variety of international protocols and conventions that deal with such matters as the illegal trade in ozone-depleting substances, the dumping and illegal transport of hazardous waste, trade in chemicals such as Persistent Organic Pollutants, and illegal dumping of oil and other wastes in oceans (Hayman and Brack, 2002). Overall, the distinction between sustainable/non-sustainable is increasingly important in terms of how harm is being framed and conceived.

Policing and prosecution

The nature of environmental harm poses a number of challenges for effective policing and hence prosecution. Environmental harm may have local, regional and global dimensions. They may be difficult to detect (as in the case of some forms of toxic pollution that is not detectable to human senses). They may demand intensive cross-jurisdictional negotiation, and even disagreement between nation-states, in regards to specific events of harm. Some harms may be highly organised and involve criminal syndicates, such as illegal fishing. Others may include a wide range of criminal actors, ranging from the individual collector of endangered species to the systematic disposal of toxic waste via third parties.

These various dimensions of harm pose particular challenges for environmental law enforcement, especially from the point of view of police interagency collaborations, the nature of investigative techniques and approaches, and the different types of knowledge required for dealing with specific kinds of environmental harm. Moreover, many of the operational matters pertaining to environmental harm are inherently international in scope and substance.

It needs to be emphasised that dealing with environmental harm will demand new ways of thinking about the world, the development of a global perspective and analysis of issues, trends and networks, and a commitment to the ‘environment’ as a priority area for concerted police intervention. The challenges faced by police in affluent countries of the West will be even more difficult for their counterparts in ‘third world’ countries, in countries undergoing rapid social and economic changes, and in countries where coercion and corruption are generally unfettered by stable institutional controls. A scoping analysis of law enforcement practices and institutions in Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia and the Philippines, for example, found common problems across the different sites (Akella and Cannon, 2004). They included:

- Poor interagency cooperation.

- Inadequate budgetary resources.

- Technical deficiencies in laws, agency policies, and procedures.

- Insufficient technical skills and knowledge.

- Lack of performance monitoring and adaptive management systems.

These challenges are global in application, although the specific nature of the challenge will vary depending upon national and regional context. Basically the message is that more investment in enforcement policy, enforcement capacity and performance management is essential regardless of jurisdiction.

Sentencing and sanctions

How courts utilise sanctions has important implications for how environmental harms are dealt with, in that enforcement practices are influenced by sanctioning practices. A comparison of European states in regard to environmental prosecution and sentencing found that the fine is the criminal penalty most commonly used in legal practice, and that the amounts imposed are relatively low on average (Faure and Heine, 2000). Especially for corporations and white-collar offenders, fines are less than effective as a deterrent— suggesting the importance of non-monetary sanctions (such as imprisonment). If the sanctions are perceived to be low or less than adequate, then this will potentially diminish environmental law enforcement efforts generally.

Even where there are severe penalties available, they may not be applied by the judiciary, especially if they are not familiar with environmental harm and its consequences. The experience in the UK has been that the trivialisation of environmental offences in the courtroom serves to impede enforcement as a whole, and to diminish the threats posed by prosecution. Specifically, the level of sentences given in courts, principally magistrate's courts, for environmental harms has been seen to be too low for them to be effective either as punishment or a deterrent (Environmental Audit Committee, 2004). Similar types of issues have been noted in respect to prosecution of fisheries offences in Australia; the existing penalty regimes are considered inadequate, and the courts too lenient.

The work of magistrates and judges in regards to environmental offences, the prospect for environmental sentencing guidelines, and the dynamics of courtroom legal argument on environmental matters are subjects worthy of continuing research and critique. Similarly, how courts respond to repeat offenders – through standard fines or escalating penalties – has important implications for achieving overall sentencing goals.

Conclusion

We conclude with the observation that the prosecution and sentencing of environmental harm really only finds purchase within particular jurisdictions and national contexts. The problem, however, is that frequently the key actors involved in such harms are global creatures, able to take advantage of different systems of regulation and legal compliance. From a global perspective, the concept of a world environmental court (or its equivalent) is an idea that demands further discussion and urgent attention.

Rob White is Professor of Sociology at the University of Tasmania, Australia. He is author of Crimes Against Nature: Environmental Criminology and Ecological Justice, 2008.

References

Akella, A. and Cannon, J. (2004), Strengthening the Weakest Links: Strategies for Improving the Enforcement of Environmental Laws Globally, Washington, DC: Center for Conservation and Government.

Beirne, P. and South, N. (2007), Issues in Green Criminology: Confronting Harms Against Environments, Humanity and Other Animals, Uffculme Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Environmental Audit Committee (2004), Environmental Crime and the Courts, London: House of Commons.

Faure, M. and Heine, G. (2000), Criminal Enforcement of Environmental Law in the European Union, Copenhagen: Danish Environmental Protection Agency.

Hayman, G. and Brack, D. (2002), International Environmental Crime: The Nature and Control of Environmental Black Markets, London: Sustainable Development Programme, Royal Institute of International Affairs.

White, R. (2008), Crimes Against Nature: Environmental Criminology and Ecological Justice, Uffculme Cullompton, UK: Willan.