I was recently invited to deliver a lecture on crime and punishment in Brazil at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies.

My exposition covered violence and mass incarceration, and how the war on drugs, the selective criminalisation of poverty and the lack of effective public policies have contributed to the development of organized crime and to a chaotic prison situation. Here, you’ll find some remarks of my talk.

Jorge Amado once wrote the Brazilian cacao lands were fertilized with blood. The history ratifies his allegory. The country has a long tradition of violence: indigenous populations were decimated, African slaves were exploited, political opponents were persecuted in two dictatorships. For centuries, specific social groups were beaten, tortured, killed, and many have disappeared.

What about the present? Is Brazil today a violent country? The data indicate that, yes, violence is systematic.

Despite a law that prohibits civilians from carrying guns, we have reached 50,000 homicides with firearms per year, with a homicide rate of 24.6/100.000 according to United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

The number of violent deaths – 279,567 between January 2011 and December 2015 – is comparable to the 256,124 deaths in the Syrian Civil War between March 2011 and November 2015. In 2015 alone, we had 58,467 violent intentional deaths: one person was violently killed every nine minutes.

The high mortality rate is selective. Most victims are poor young black men. Considering the uniformity of the victims’ characteristics and the systematic form of the executions, several reports have depicted this slaughter as genocide. And this can be attributed to the consequences of social inequality and especially to the war on drugs.

One of the outcomes of drug criminalization is the opportunity for the emergence of criminal organizations and factions, which engage in wars against each other, generating more crimes and a shameful death toll.

Another outcome is the lethal performance of the police. The Brazilian police kill too many people. In 2015, there were 3,320 victims of police interventions. 358 police officers were killed in the same year. All of this is legitimated by an extremely punitive culture: a recent research revealed that 57 per cent of the Brazilian population believe ‘a good criminal is a dead criminal’.

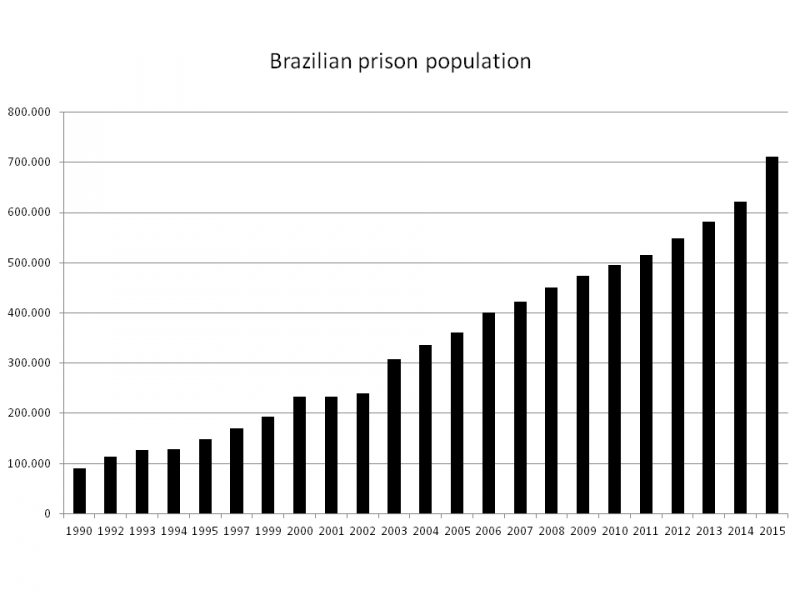

And how have we dealt with it in Brazil? We arrest people. We keep more than 700,000 people arrested, in a very precarious system with the formal capacity of little more than half of this number (357,219). It means that we have an occupation rate of 200 per cent. If we add the unfulfilled arrest warrants (over 370,000), we will have a new deficit of more than 700,000 beds.

This explains the shocking situation recently reported by the media: with an overloaded capacity, police had to keep remand prisoners in police cars, and even chained to street dustbins, in the southern city of Porto Alegre.

But, can we talk about mass incarceration in Brazil? If we analyze this imprisonment phenomenon according to the two features of mass imprisonment, according to David Garland, the answer is: yes, we do have mass incarceration in Brazil.

First, it is evident that the rate of imprisonment and the size of prison population is well above the country’s historical pattern and the comparative analysis with other comparable countries.

The second feature noted by Garland is the systematic imprisonment of groups of the population.

The prison censuses indicate Brazilian prison population is constituted mostly by uneducated poor young black men:

- 75 per cent of the prisoners have only complete primary education (less than one per cent had completed higher education)

- 62 per cent are black (or mulatto) and 94 per cent are men.

By contrast, of those responsible for prosecution:

- More than half (54 per cent) of federal prosecutors are post-graduate, mostly white (80 per cent) men (71 per cent).

- State prosecutors and judges have similar patterns.

These contrasts make it apparent that a social group is accused, prosecuted and sentenced by another social group; the two almost totally distinct from each other.

Mass incarceration, promoted by punitive criminal policies, in extremely precarious structural conditions, has contributed to the emergence of criminal factions and commandos that govern the incarcerated population and the organized crime today.

The two most important groups have the origins in and emerged as a consequence of, atrocities perpetrated by the State. These are the Comando Vermelho (CV) and the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC).

After a two-decade truce between these two groups ended last year, prisoners’ struggles resulted in more than 110 violent deaths in many prison facilities during January 2017.

The aftermath of these mass killings evidences two things. First, these massacres won’t stop now, and we can expect to have more killings and many other crimes. Both commandos are disputing prison and urban spaces, particularly interested in controlling the cocaine trail across Amazon.

Second, from the government response to this crisis, we are witnessing what I’d call – drawing on Foucault’s expression – a thanatopolitics. The State does not kill directly unwanted groups of individuals. Rather, the State lets them die, in this case reinforcing the worst conditions for these massacres to happen.