Young people and social exclusion: a multidimensional problem

Antonia Keung explains social exclusion

Social exclusion impacts not only those directly affected but also society more broadly, and is estimated to cost billions of pounds a year in welfare support, loss of earnings, and taxation. This article focuses on the issue of social exclusion and young people aged 16 to 24. It explores why social exclusion is important, how many young people are affected, what are the contributing risks and how those affected are distributed between the different risk groups.

Social exclusion describes a combination of problems. Levitas et al. (2007) define social exclusion as a complex and multidimensional process that can lead to disadvantages in three main dimensions of people’s lives: material and relational resources, participation, and quality of life. These are often associated and the experience of exclusion in any one dimension can reinforce another, leading to a number of disadvantages. For instance, individuals can face a combination of problems including having no/low qualification, unemployment, poverty, family breakdown, poor housing, ill health, and crime.

Young people between 16 and 24 years are facing a number of challenges in their transition to adulthood. One of the major transitions for this age group would be the transition from school to work or higher education. However, a proportion of young people in England fail to make such transitions and ended up not in employment, education, or training (NEET). This is a common form of social exclusion amongst young people.

The impacts of NEET on young people are well documented. It can have a detrimental effect on young people’s well being and future outcomes. Research shows that young people in the NEET category often have a low sense of control over life and are also discontent with life. This is especially so for young women (see Bynner and Parsons, 2002). In terms of future outcomes, non participation in employment, education, or training can lead to a number of short and long-term negative consequences including unemployment, poor health, early parenting, alcohol and substance misuse, and involvement in criminal activity (Coles et al., 2002). Additionally, the experience of NEET in one’s early life can reduce his/her lifetime employment prospects. For example, research found that unemployment at the age of 18 in young people with low or no qualifications was linked to lower earning in later life (ibid). Furthermore, without effective interventions the experience of social exclusion can pass on from one generation to the next (ibid).

In addition to the impact on young people themselves, NEET can also represent a substantial cost to the society. These costs include: welfare cost and loss in financial contributions to the economy and public finance. Godfrey et al. (2002) provide a conservative estimation of £8.1 billion of additional public finance spent on dealing with consequences of NEET. In current terms, this figure is likely to be substantially higher due to inflation and increase in the size of NEET group during the economic recession.

Approximately 895,000 young people aged 16-24 were NEET during the final quarter of 2009, corresponding to 14.8 per cent of all 16-24 year-olds (Department for Children, Schools and Families [DCSF], 2010). This represents an increase of 4.8 per cent over the same quarter in 2008 with a figure of 854,000 (DCSF, 2010). The NEET group mainly includes: care leavers; youth homeless; runaway youth, truant youth or those excluded from school; college drop-outs; young people with special education needs or disabilities; or suffering from mental health problems, and/or drugs/alcohol abuse; teenage parents; carers; and young offenders (Coles et al., 2002).

A recent study published by the Social Exclusion Task Force (2009) explored the risks of social exclusion among people and families across key life stages. Part of the study, conducted by the University of York (Cusworth et al., 2009), focused on youth and young adulthood and conducted secondary analysis of existing datasets from the Family Resources Surveys (FRS) and the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). As both are household surveys, people who are not living in households were excluded. Thus, some of the risk groups such as young people who are ‘looked after’, homeless, or are offenders are not included in the datasets.

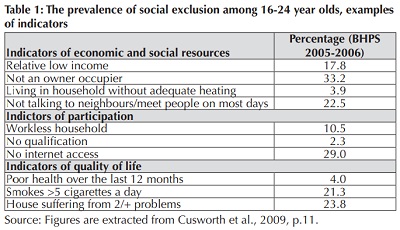

As mentioned earlier, social exclusion is multidimensional. Table 1 provides examples of figures on the prevalence of young people experiencing different forms of risks leading to social exclusion. These figures indicate that social exclusion affects a substantial proportion of young people.

The results of the analysis suggest that young women generally experienced a higher level of risks than young men. Young people living with a lone parent, or independently with their own children were also at a higher risk and were also more likely than other young people to have little educational qualifications and be in the NEET group. Moreover, young people with these three characteristics were also more prone to multiple risks, as were the older young people, and those who were social and private tenants, living in areas with higher levels of deprivation or living in urban areas (compared to those living in villages).

Although analysis of the BHPS data found no specific trend in singular risk between the periods of 2001/2002 and 2005/2006, the results show the proportion of those who experienced seven or more risks fell from around 21 per cent to just less than 16 per cent over the period. Young people whose risk of disadvantage persisted over the entire five year period of the study included those living in households that did not have homeownership, internet connection, anyone in employment; themselves smoked more than five cigarettes a day; or had no qualifications or training.

In order to investigate how experience of social exclusion changes over time, the study analysed young people’s movement between different clusters of disadvantage: ‘low ‘medium’, and ‘high’ based on the proportion of those who were at risk on 15 indicators identified to characterise social exclusion in different dimensions. The ‘highly disadvantaged’ cluster contained young people poor on all indicators or all but one indicator, while the ‘low disadvantaged’ cluster had the lowest proportion of respondents poor on any of the indicators. The study found that most of the affected were in the ‘medium disadvantage’ cluster. On average they remained there for 1.4 years. Those in the ‘high disadvantaged’ cluster remained there on average for the shortest period of 1.2 years, whilst those in ‘low disadvantaged’ cluster remained there for the longest average period of 1.5 years. In general, the odds of moving from the ‘medium’ to ‘high disadvantage’ cluster were higher for those who did not live with a partner than those who did. Additionally, among young people who experienced disadvantages, those who lived with two parents were about twice as likely to improve their circumstances, i.e. move out from the ‘medium’ to the ‘low disadvantage’ cluster, than those who lived independently of their parents.

The research also indicated links between adolescent experience and disadvantage in young adulthood. Results from the longitudinal analysis of the BHPS showed that young people, having lived between age 11 and 15 in households which were in receipt of income support, were associated with higher odds of disadvantage at age 20 to 24. This finding supported the hypothesis of the intergenerational cycle of poverty. Furthermore, the study also found that higher self-esteem for teenage boys and girls during adolescence can help to prevent later disadvantage.

In summary, social exclusion affects a substantial proportion of young people in England and it entails a significant cost to the society as well as the quality of life of those affected. Research shows a clear tendency of an intergenerational cycle of social exclusion and it indicates that social exclusion can be both the cause and consequence of disadvantage for young people. In order to break that cycle, government support for families is needed, in particular for young families living independently with children and lone parent families.

Dr Antonia Keung is a Research Fellow, Department of Social Policy and Social Work, University of York.

References

Bynner, J. and Parsons, S. (2002), ‘Social exclusion and the transition from school to work: The case of young people not in education, employment or training’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, pp.289-309.

Coles, B., Hutton, S., Bradshaw, J., Craig, G. Godfrey, C., and Johnson, J. (2002), Literature Review of the Cost of Being ‘Not in Education, Employment or Training’ at Age 16-18, Research Report, 347, Nottingham: Department for Education and Skills.

Cusworth, L., Bradshaw, J., Coles, B., Keung, A., and Chzhen, Y. (2009), Understanding the Risks of Social Exclusion Across the Life Course: Youth and Young Adulthood, SETF and SPRU. Available at www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/ media/226116/youth.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2010).

Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) (2010), NEET Statistics: Quarterly Brief. www.dcsf.gov.uk/ rsgateway/DB/STR/d000913/index.shtml (accessed 8 March 2010).

Godfrey, C., Hutton, S., Bradshaw, J., Coles, B., Craig, C., and Johnson, J. (2002), Estimating the Cost of Being ‘Not in Education, Employment or Training’ at Age 16-18, DFEE, University of York, and University of Hull.

Levitas, R., Pantazis, C., Fahmy, E., Gordon, D., Lloyd, E., and Patsios, D. (2007), The Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Social Exclusion, Bristol University.

Social Exclusion Task Force (2009), Understanding the Risks of Social Exclusion across the Life Course, research project. www.cabinetoffice.gov. uk/social_exclusion_task_force/lifecourse.aspx (accessed 15 March 2010).