Sarah Reed’s Christmas card to her mother read: “Mum, this is just to say Merry Xmas ... PS. Get me out of jail.” It was one of a number of appeals from Sarah to her family in the last weeks of her life. “She kept writing to me and other family members saying, ‘Please help me to get out of here; I shouldn’t be in here; I’m not being treated,” her mother, Marylin Reed, says. “Her priority in every letter was: ‘I need my medication.’”

When Marylin visited her daughter in Holloway prison on 2 January, she was dismayed to find Sarah looking unwell, and behaving strangely. She remembers a prison guard asking her: “Have you got any idea what’s wrong with her?” It was a disconcerting question, because prison staff should have known that Sarah Reed had serious, long-standing mental health problems.

Nine days later, Sarah, 32, was found dead in her cell. The family was told first by the prison that she was found hanging, and later that she was found lying on her bed, with a “sophisticated ligature”. The precise sequence of events in the months, days and hours leading up to her death will remain unclear until an inquest is held later this year, but already the tragedy has raised important (if depressingly familiar) questions about the treatment of people with serious mental illness by the criminal justice system, and how that intersects with the institutional racism faced by black Britons.

What is particularly disturbing about Sarah’s case, is that her name was already well-known to race and mental health campaigners. In 2012, she was at the centre of a police brutality case, when a Metropolitan Police constable, James Kiddie, was caught on CCTV, yanking her by the hair, dragging her across the floor, pressing on her neck and punching her several times in the head. The footage of the assault is very painful to watch. Kiddie, who accused her of shoplifting, was convicted of assault, dismissed from his job, and given 150 hours community service.

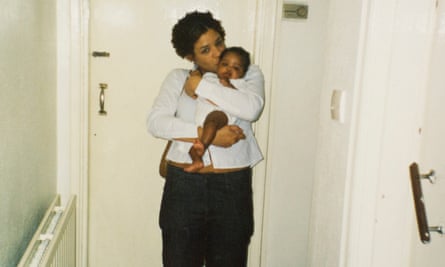

Reed was already struggling with mental health problems when the assault happened; her family say she had never fully recovered from the death of her nine-month-old daughter in 2003, after months in hospital and a distressing battle with illness. But the assault had a profoundly negative impact on Sarah’s state of mind, and left her frightened of tall, Caucasian men, often feeling so vulnerable that she would return home to sleep in her mother’s bed for protection. She spent chunks of the intervening years sectioned in hospital, and struggled to rebuild her life.

The story of the final years of Sarah Reed’s life comes in chapters, marking repeated failings by the state, as different institutions missed opportunities to help her. Speaking publicly about her daughter’s death for the first time, Marylin says she feels Sarah was the victim of a “collective failure” by prison officers, doctors, social workers and lawyers. “I knocked on all of those doors, I pleaded with all of them. I believe she was failed by many, and I was ignored by many, especially building up to the time of her dying. My voice hit the floor and nobody answered,” she says.

The last meeting she had with Sarah convinced Marylin that Holloway prison was not the right place for her unwell daughter. Unusually, rather than taking her to the visitors’ room, guards escorted Marylin into the heart of the prison, to the wing where Sarah was living; they met in a room three doors away from the single cell where she was being held. The officers said they were hoping that Marylin’s visit might help Sarah become more co-operative.

She was distressed by her daughter’s appearance; she had put on weight, and had dark patches beneath her eyes. “I remember asking her: ‘What’s going on with your eyes?’ She said: ‘I’m not able to sleep. I’ve asked for sleeping tablets, and I’ve not been given anything.’” They had half an hour together. “We were just chatting. She was asking how our Christmas was. She explained to me that she had not had any new year or Christmas, that her TV had been removed.”

Marylin gave her some Starburst sweets that she had bought in the prison waiting room. She was worried by the way Sarah was dozing off. “She was talking to me and then she looked at me and she started to cry for no reason. “I said: ‘Why are you crying?’

“She said: ‘I’m crying because you’re crying.’

“I said: ‘I’m not crying.’

“She said: ‘I think you’re crying Mum.’”

A prison officer came to tell her that they had five more minutes together.

“I remember saying to her: ‘I’ve not even had a chance to see you.’ And then I hugged her and said: ‘Try and keep your head up, because in about a week you should be coming home because we’ve changed solicitor, and they believe that because you’ve been in since October, there is a chance that you will be coming home, next week, Monday.’

“I hugged her and I said: ‘I love you.’ And she said, ‘I love you, too’. Normally she was chatty. Normally she gives me a list of things to do. But that particular day she didn’t really say a great deal. She seemed not the norm. I went on hugging her. Instead of embracing me, like she normally would, she sort of leaned away, took a deep breath, dropped her hands, looked around, and said to me: ‘Bye.’

“That was the last time I saw her.”

Before being sent to prison, Sarah had been receiving treatment at home as a mental health patient, with regular visits from medical staff, under a care in the community scheme. Until the inquest, we won’t know what treatment she was getting in prison; all we know is that she felt she was not being helped.

Marylin told the prison guard who took her back to the main part of the prison that she was worried about her daughter. “I said to him: ‘She seems like she is in distress, trying to cope.’ I asked: ‘What’s going on with her medication?’”

The prison guard seemed to suggest that she was not being treated as someone who was seriously unwell. “He said she’s being treated as a normal prisoner. I said: ‘How can that be?’ He said: ‘We have tried to tell our medical department that maybe she is in need of something.’

“His advice was: ‘When you get back on the outside, maybe on Monday morning, you can contact her medical team outside, and get them to contact our medical team, to let them know that she’s in need of something,’ because, he said, ‘we’re not being listened to’.

“He said: ‘We deal with restraint and maintaining the law. We’re not designed to deal with health issues.’”

Marylin set out to get her daughter help, but in the end there wasn’t time. At 9.10pm on Monday 11 January, she was called by the prison, and told that her daughter had been found dead. She went to Holloway with her son and her mother. Despite repeated requests, they were not allowed to see the body. The coroner’s officer told them that she wanted to “spare them the trauma of looking at her”. They were upset by the treatment they received at the prison, and felt that one officer was laughing at them. It was three days before they were allowed to see her. “I felt like she was still being treated as if she was a living prisoner, and that we as her family had no access, no rights.”

The family is at the beginning now of what will be a long fight for answers, but it is already clear that there is a huge determination by campaigners that Sarah Reed’s name will not be forgotten. If Sarah was neglected and ignored during her lifetime, there is little chance that her death will be overlooked.

On the night following Sarah’s funeral, hundreds gathered for a vigil organised by Black Sox, a black-led social movement, outside the red brick walls of Holloway. Sarah’s name was marked out on the pavement in candles. Through the window of the jail, two prison guards could be seen in silhouette, peering out as crowds chanted: “Say her name: Sarah Reed. Black Lives Matter.”

Racial equality campaigners were instrumental in getting Sarah’s story out, after the family’s efforts to speak to the media initially fell on deaf ears, and prominent figures in the Black Lives Matter movement in the US began to pay attention.

Lee Jasper, the racial equality campaigner, who helped break the story on his blog, and who is co-ordinating the Sarah Reed justice campaign through Facebook, says: “This case represents elements of racism, sexism and police brutality too often faced by black women within the system. Both in the US and here in the UK, the Black Lives Matter movement is rising, and Sarah’s tragic case will elevate the issue of the treatment of black women in the criminal justice system. Sarah should never have been in prison, period.”

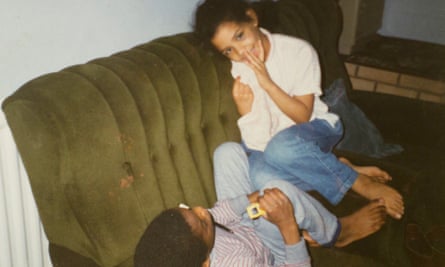

Before she tries to unpick the complicated series of events that led to Sarah’s illness and death, Marylin Reed pays tribute to her daughter, a woman whom she describes as “thoughtful’ and “warm, kind and loving”, someone who loved to dress up in unusual, beautiful clothes, and who liked to come round with clothes to dress up her mother, and her disabled sister. She was very thoughtful, someone who “was always wanting to include others and help others”.

“On her good days I was really proud of her. I used to say to her on those days: ‘You’re beautiful. Try to lift your head above life, the things you’ve experienced. Try and find your way back.’ Unfortunately, she had more bad days than good,” Marylin says.

By the time she died, Sarah had experienced enough in her life to make lifting her head high a struggle. Her baby had died from muscular atrophy after several operations and a life spent mainly in hospital. The hospice where the baby died then made the disturbing decision to give Sarah and the father their daughter’s body wrapped in a sheet to take to the undertaker in a taxi. Marylin says: “Sarah became withdrawn immediately. I tried to get her bereavement counselling. They were devastated.”

Then there was the police attack, which disturbed her profoundly. “She was horrified. It affected her because she wasn’t raised with corporal punishment of any kind. She used to say whenever she would see a very large male, tall male, it would make her feel nervous, insecure and frightened,” Marylin says. “She felt more nervous about males, on top of everything else she had gone through, especially Caucasian males.”

After the assault, Sarah was more unwell than well, and spent several chunks of time in institutions. Sometimes she would retreat home to visit her mother, and her own teenage daughter (elder sister to the girl who died). “She had days when she was in crisis when she would need to be with me, she would end up sleeping with me, on my bed. I would say, ‘Sarah, you’re a bit big to be sleeping on my bed.’ That was Sar. She was always wanting cuddles and kisses from everyone.”

Alongside the well-documented disproportionality of police attention that black Britons face is a troubling relationship between the community and mental health services. Figures from last year suggest that black and black British people were more likely than any other ethnic group to be detained under the Mental Health Act, a statistic that the mental health charity Mind attributed to stigma and discrimination, and a failure to provide services that were accessible to non-white communities

But by the middle of last year Sarah’s family began to feel she was finally getting some new stability in her life. Although while sectioned in 2014 she had been arrested and charged with GBH, she had been bailed and housed in a studio flat close to her mother and daughter. She was having weekly visits from a mental health team. Her case was ongoing, but Sarah told her family she had acted in self-defence against a sexual assault.

Then, unexpectedly, at a hearing for the case in October 2015, she was remanded into custody and sent to Holloway. Her family is still not clear why she was imprisoned then, although they believe that further psychiatric assessment had been ordered by the court to establish whether she was fit to plead. If this was the case, they are confused about why prison was thought to be a better place for this than hospital.

Marylin was very distressed when she discovered that Sarah had been sent to prison. “I was devastated, because it didn’t make sense,” she says. Everything had just begun to come together for her daughter. “Everyone got their act together, getting her a home, getting her care in the community,” she says.

A month and a half after she arrived, the government announced that Holloway was going to close and the site redeveloped for flats. It is not clear what effect, if any, this had on the daily running of the prison. Marylin notes though that she twice turned up at Holloway expecting to see her daughter, and was told that no appointment had been booked. She doesn’t know if this was down to confusion on the part of her daughter or a mistake by the prison.

“The time that I did get let through the doors I was told by the women at the desk: ‘Are you aware that we are closing down?’” She isn’t sure why they told her this. The Ministry of Justice says that Holloway is operating as normal ahead of its closure. A Prison Service spokesperson said in a statement: “Our sympathies are with the family and friends of Sarah Reed. As with all deaths in custody, the independent Prisons and Probation Ombudsman will conduct an investigation. We take our duty to keep prisoners safe extremely seriously. On any given day, prison staff provide crucial care to over 2,000 prisoners at risk of self-harming.”

But that confidence is not shared by the Prison Officers Association. General secretary Steve Gillian said: “We’ve been saying for some time that there has been a large increase in deaths in custody and we put it down to a lack of resources, a lack of training. Prisoners who have mental health issues are not being diverted from prison and we don’t have adequate resources or training. Bear in mind there are 7,000 fewer prison officers now than there were in 2010 due to budget cuts, and a record number of prisoners.”

The Reed family’s solicitor, Sophie Naftalin, says: “Sarah Reed was a vulnerable young mother whose life and death provide a powerful illustration of how the criminal justice system fails people with mental health problems. Her family have many questions about how Sarah was allowed to die in custody and whether it was appropriate for her to be in prison in the first instance.”

Campaigners for prison reform are despondent about rising numbers of deaths in custody. Last year five women killed themselves in prison, the highest number since 2007 when concerted action was taken to help vulnerable women in prison. Two more died in January, according to the campaign group Inquest, and there was an 11% rise in self-harm by women in prison in 2015. Across the prison estate self-inflicted deaths are at a record high, with 89 in England and Wales in 2015.

Responding to the report, a Ministry of Justice spokesperson said: “As the prime minister said last week, prisons are failing to treat prisoners’ mental health problems as well as they should ... That is why the prime minister announced an overhaul of how mental health is treated in prisons.”

Chief executive of Inquest, Deborah Coles, who advised on the 2007 Corston report, which examined how to deal with vulnerable women in custody, and introduced (for a while) improvements, says: “The fundamental question is why women like Sarah Reed, with a well-documented history of mental illness, was ever imprisoned in the first place. The investigation into her death must consider the role of the Crown Prosecution Service, courts, mental health services and prison and whether their failings contributed to her death. The state’s responsibility for the deaths go beyond the prison walls and extend to failures in mental health and substance abuse provision, sentencing policies and the failure to implement Corston and invest in alternatives to custody.”

Most of all, Marylin is angry at the failure of those who were responsible for Sarah Reed to deal adequately with her mental health needs. She hopes that at least some lessons may be learned.

“I’d like the UK to overhaul how they treat people with mental health issues. People don’t get up in the morning and decide to have mental health issues. Mental health is like all other sicknesses. I would like from my daughter’s death, that lessons be learned and that if anybody else goes into the hands of Holloway, any prison or even a hospital, that they be treated as human, and be assessed and their needs be met.

“I personally don’t believe that prison is the place for anyone with mental health issues. I would like, if anything comes from what’s happened to my daughter, that it would save the life of another [person], who shouldn’t be in a prison.”